Your cart is currently empty!

The Backstory of David Bohm’s Dialogue

the December 2020 issue of Pari Perspectives.

Introduction and Overview

For many of you, your introduction to David Bohm came through his scientific contributions, and, in the other presentations at this conference, we’ve had deep reminders of the magnitude of those contributions. My own introduction came through a different route, not from the orientation of science, for my background in science falls far short of that of most of you. My entrée to Bohm came through the process of his signature social change process that he called dialogue. In the description which follows we will go into Bohm’s meaning of the word dialogue, and will distinguish it from its common usage.

Several of you also share an interest in dialogue and, given the breadth of Bohm’s thinking, you may have entered this realm from a number of vantage points. So, surely there are those of you who would take a different orientation or approach to looking into our topic—the history of dialogue. From my conversations with some of you here, I know you started your journey into dialogue through an interest in Bohm’s work with Krishnamurti. I haven’t yet delved into Bohm and Krishnamurti’s long friendship and conversations together, and so cannot speak with any depth about the influence of Krishnamurti on Bohm, except to say that he greatly impacted the intent for dialogue. While we will not go deeply into that aspect of dialogue, I can, hopefully, take you on a journey describing a model or methodology of dialogue David Bohm inherited and how he built upon it to become what many of us have come to think of as Bohmian dialogue.

Early in my exploration of Bohmian dialogue, I thought that Bohm was its originator, its creator, but after much digging into the early starts of this process, my contention is that David Bohm did not develop from scratch the form of dialogue which carries his name. Now, that came as a shock to me as well as to other folks. Through my research, I’ve come to see that he inherited a model or methodology of dialogue and then built into it other rich areas of inquiry, such as his deep delving into the process of thought and, of course, his unique work in quantum theory and theoretical physics. So, what I want to share with you is some of those early methodological starting points for dialogue as he first came into them and to let you backtrack along with me.

Before diving in, let me give you a brief overview of my presentation. To set the context, I’d like to share a bit about myself and how I came to be intrigued with what I’ve called the ‘backstory’ of dialogue. Then, to start us all off with a similar understanding of David Bohm’s dialogue, I’ll share some of the characteristics that he said were the essence of dialogue. And finally, I’ll introduce the individuals who form the lineage of Bohm’s methodology for dialogue and identify the traces of their thought in Bohm’s.

Setting the Context

For me this is a historical journey which came out of my early learning about and the practice of dialogue. People practise dialogue in very different ways, and I want to give you a taste of what my practice has been and to give us all a common starting point. Early in my career, I had gone back to university wanting to explore how social change happens. I had had some rather intense experiences that acquainted me with social change, but that experience was inarticulate. I figured that if I went to business school, there I could learn what corporations knew about how change happened. I wanted to know what change agents actually do. How does the process of change work? My first encounter with the work of David Bohm came when I studied systems theory.

Shortly after finishing those educational pursuits, I worked as the administrator of a large health care system. One of the long-term care facilities in that system was having significant problems. For example, absenteeism was a terrible problem. We had to hire one-and-a-half, full-time-equivalent nurses to keep one nurse on the floor. The absenteeism rate was so high that if one nurse didn’t show up for duty, a nurse from the previous shift had to stay over for a double shift. So, it was a really huge issue.

We had tried many interventions to resolve the various problems, but all those interventions had failed. At a particularly troublesome point, the medical director and I sat down to plan what to do next. By then, I had exhausted everything my management education had taught me, except for one thing. By that time, I had participated in training for David Bohm’s dialogue process, and that was the only option I could think of which potentially would be a strong enough intervention to penetrate to the heart of the problems. But, it was risky, and it would have to be conducted for a long time—a year—I predicted.

The powers-that-be approved. I trained all 170 staff members of that facility in a day-long course on dialogue. And then I asked for a cross-section of thirty employees who would work with me over a year. Much to my surprise, eighty-some staff volunteered—about half of the whole staff. With such a large number, we were able to create multiple cross-sectional groups including every shift, level, job and discipline. It was one of the most mind-bending years of my life! I want to give you two examples that set the stage for my researching the methodology that Bohm inherited in his development of dialogue.

First, a description of our dialoguing about the problem of the extremely high absenteeism rate. One day, as a dialogue group was beginning, one of the maintenance men came in. He was a real salt-of-the-earth kind of guy who had worked in the facility for forty years, a person who was usually quite unemotional and stoic. But this day he looked grey and very distressed when he came in. As we sat down, I said to him, ‘What’s going on with you, you look so sad?’ He was very close to tears, but with difficulty he said, ‘Mr Jones [a patient] died during the night. And I used to go see him every day. I did that every day for the past ten or twelve years. He was like a father to me. And, he died.’ The group became hushed. After a while, one of the nurses said, ‘You know, some days I pull into the parking lot, I put my car in park, and I sit there and I say to myself, who’s going to die today? I can’t stand it, so I put my car back in drive and I go home and call in sick.’ And then someone else said something similar, and someone else, and someone else.

All of our Human Resources processes, all of our high and intelligent interventions that had been an attempt to deal with the absenteeism had failed to identify the real problem. What had emerged in this group of people who, through participation in the dialogue group, had come to trust each other was a simple but profound human issue: GRIEF! The patients that these staff took care of day in and day out, patients they loved, died. It was, after all, a long-term care facility for elderly people. At the bottom of this extreme absenteeism issue, so far buried under the surface of their awareness, their human hearts were entangled! And what then was the resolution? We began offering grief therapy for staff and more outward, humane understanding of those caregivers who hurt when their patients had died. We would never have found the core underlying problem without dialogue.

So that’s one example of the deep power of dialogue to go under the surface and to unearth those things that our psyches know at some level but that we can’t articulate. The other example is not such an easy one. Following the sessions, people came to those of us conducting the dialogue and said things like, ‘The perception came to my mind, while I was sitting there, of being sexually abused when I was three.’ Others shared deeply buried early life experiences that surfaced during the dialogues, experiences that were unrelated to the topic around which the dialogue session had been oriented. We had begun unearthing and evoking issues that were not anticipated; they were not organizational issues, but rather were very deep psychological issues that needed professional intervention. That bothered me a lot! I didn’t know what we facilitators had done that would evoke that kind of response. We were able to refer these folks to the professional resources appropriate to their issues, but the concern stuck in my mind.

Those two issues—the power of dialogue to go very deeply and to evoke the issues under the surface and, secondly, some of the risks that go into doing dialogue if you’re not prepared for the consequences that can arise—these two concerns catalysed in me a quest for the history and the underlying methodology of dialogue. Perhaps you could say I wanted to dialogue the underlying premises and processes of dialogue, to dig under the surface and to find the drivers of dialogue.

In previous days here, David Schrum talked about the way in which the brain and consciousness work. His charts hung on the walls around us, and I suggest that you ponder the similarities between David’s presentation and what I will be sharing.

When I have shared this particular research effort of teasing out the backstory of dialogue, some folks have found it irritating. David Bohm has been such a prophet that to some these thoughts suggesting Bohm wasn’t the originator of this form of dialogue, seem heretical. Well, it is not at all my intent to discredit David Bohm, but I suggest that there are good reasons for looking back into dialogue’s origins.

I’d like to think that when practitioners have enough awareness of Bohmian dialogue’s dynamics and origins, they will more wisely construct their own working models of it. I spoke a moment ago of one of my dialogue interventions that evoked psychological issues. At the time I didn’t know why that happened. My contention is that it is wise to know such things can arise during dialogue, so that you make good choices in deploying your skills and your capacities and thus to safely manage on behalf of your clientele. Deep knowledge of dialogue’s dynamics and origins also helps build a coherent methodology. I see all sorts of variations of supposed dialogue models in my work, and some of them are a hodgepodge of this, that and the other. Some of what is called dialogue just doesn’t fit into the process of dialogue that Bohm would have advocated.

A Description of Dialogue

To start with, let’s look at Bohm’s intentions and the characteristics of dialogue pulled from his own writing so that we start with his ideas of a standard for dialogue.

Bohm’s Orientation to Social Change

Very fortunately for me, for a few years David Peat was my mentor and kept me closely on track with Bohm’s thinking. From Peat’s research we can see that even as a child, David Bohm himself talked about his growing up in a fractured family situation that led him to a lifelong search for wholeness. Also, he grew up in the 1920’s, seeing his childhood friends’ families suffer when the fathers lost their jobs in the coalmines of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania. And, there were deep schisms in the community regarding ethnicity. From the get-go, these early life difficulties created in David Bohm a commitment to bringing about a much healthier society, and that commitment flows through all of his life endeavours. Seeing the discord around him as an adult, he worried that the needed societal change would not happen on its own. Here are his words: ‘People say, “All we really need is love.” If there were universal love, all would go well. But we don’t appear to have it. So, we have to find a way that works1.’

Bohm was very deeply concerned about using his life in science not only to advance theoretical physics but also to find ways to help the world mend itself. He said the things that we face today are different than they’ve ever been.

The challenge that faces humanity is unique, for it has never occurred before. Clearly a new kind of creative surge is needed to meet it. This has to include not just a new way of doing science but a new approach to society, and even more, a new kind of consciousness2.

Keep in mind he was someone who had helped develop the science instrumental in creating the atomic bomb. He had lived at the end of the First World War and had seen the Great Depression. He had lived through the Second World War and he had been through some difficult personal issues. So, he had experienced a heavy load of societal trauma. From that, he concluded that a new kind of consciousness was required. Never before have we confronted the things we’re confronting today, he said. Our way of thinking must change. Dialogue, he proposed, might help bring about that change

Key Descriptors of Dialogue

Again, I want us to start with a common picture of dialogue, especially if some of you here are more familiar with his science than with his ideas about social change. Here are some of Bohm’s key descriptors of dialogue to give us a shared orientation. Bohm would say that dialogue

- deals with ‘wholes’ rather than ’fragments,’

- is based on listening,

- digs safely into individual and group assumptions,

- asks for suspension of judgements of one’s own and others’ judgements,

- has no outcome other than inquiry into what is beneath the surface of thought, has no agenda and no purpose other than observing what comes up during the conversation,

- doesn’t expect agreement or acceptance of others’ points of view, just understanding, and

- creates meaning.

And he also said that there are things that dialogue isn’t. The statements below are in his own words, mainly from his book, On Dialogue. I have added a few of my original reactions as I read these ‘Do not’s.’

- ‘The group is not mainly for the sake of personal problems; it’s mainly a cultural question3.’

Why, I wondered, would he be making reference to ‘personal problems?’ That seemed outside the context of a social change process.

- ‘A dialogue group is not a therapy group; we are not trying to cure anyone here4.

This one in particular made no sense to me. As in the first ‘Do not’ bullet above, in the midst of a social change process, why would he assert that he’s not doing therapy?

- ‘In a dialogue group we are not going to decide what to do about anything. This is crucial. Otherwise we are not free. We must have an empty space where we are not obliged to do anything, nor to come to any conclusions, nor to say anything or not say anything. It’s open and free. It’s an empty space5.’

There’s no decision-making. The freedom comes from the open, empty space, which we rarely experience in our lives—and that was the critical issue. Now you can start to see that when we do dialogue in corporate settings, we are already violating Bohm’s intent.

- ‘In dialogue there is no absolute purpose. We may set up relative purposes for investigation, but we are not wedded to a particular purpose … our purpose is really to communicate coherently in truth, if you want to call that a purpose6.’

- ‘Conviction and persuasion are not called for in a dialogue. The word “convince” means to win, and the word “persuade” is similar. It’s based on the same root as are “suave” and “sweet.” People sometimes try to persuade by sweet talk or to convince by strong talk. Both come to the same thing, though, and neither of them is relevant. There’s no point in being persuaded or convinced. That’s not really coherent or rational. If something is right, you don’t need to be persuaded. If somebody has to persuade you, then there is probably some doubt about it7.’

- ‘Dialogue is not “discussion,” a word that shares its root meaning with “percussion” and “concussion,” both of which involve breaking things up. Nor is it “debate”8’.

Bohm makes a big distinction between discussion and dialogue. If you’ve read Bohm’s works, you know he loves to go back to the etymology of words. That’s where he starts making this distinction. Discussion, he says comes from the Latin root, quatere, to shake or to strike. Words having that same Latin root are percussion and concussion. In essence, the word discussion emphasizes analysis, winners and losers, and breaking things apar9. It’s about competition and hierarchy.

Dialogue, on the other hand, is composed of two words—dia and logos—from which Bohm builds together the meaning: ‘the word or the meaning of the word + Dia = through10.’ In his words, dialogue is ‘a stream of meaningflowing among and through and between us, a flow of meaning in the whole group, out of which may emerge some new understanding. It’s something new, which may not have been in the starting point at all. It’s something creative.’ Dialogue, then, is about equity among participants, about freedom to pursue a hunch that emerges from the group and to follow it deeply into its hiding places within our not-yet-articulated awareness. Dialogue is not linear, but circular.

So, discussion breaks things apart. Of course, it’s a useful process in certain circumstances. But, dialogue builds things together, bringing them back to their original wholeness and to articulateness.

The Lineage of Dialogue

With some common orientation to Bohm’s guidance on dialogue, I’d like now to shift to my original contention, that Bohm inherited a model of a group process that he refocused to achieve his intention of creating social change.

There are particular folks who influenced the model of dialogue that David Bohm inherited. I think of a model or platform much as I think of a platform of software or social media. The software or social media provide a structure and process to which you add your content. What David Bohm inherited was a methodology or model for working with groups, and then he added to this methodological model his theoretical physics, his work on thought, his deep pondering with Krishnamurti, etc. What I’m attempting to illuminate is specifically what he started with. With this as a starting place, we can identify Bohm’s unique contributions. Let’s start by asking, ‘Where did he start? What was the conceptual methodological model of group conversation that he was initiated into?’

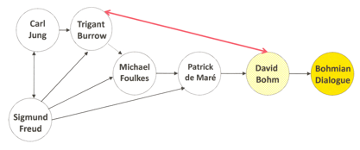

My research has shown that there were three particular individuals who contributed to the methodological model which Bohm inherited, and I refer to the linkages and building upon each other’s work as the lineage of dialogue. Working backwards through time, the individual closest to Bohm and from whom Bohm received this methodological model was Patrick de Maré.

Patrick de Maré

The first member of this line of transmission, the person most closely associated with Bohm, is Patrick de Maré (January 27, 1916–February 17, 2008), a British psychiatrist who treated David Bohm in the latter years of his life. We know from David Peat’s biography that Bohm had suffered from depression, and there were points in time when he needed psychiatric assistance. Patrick de Maré was one of his psychiatrists. About the same age, they became great friends. Both of them had a deep interest in Marx’s philosophy and a shared interest in social change. I’ve had some conversations with still-living friends of de Maré who say he was both a Catholic and a Communist, certainly an unusual combination.

De Maré served in the British Royal Medical Corps, where he had been trained in psychiatry by Wilfred Bion and John Rickman, significant innovators in psychiatric group work. Serving on the battle front, de Maré saw horrible trauma as soldiers came back from the war. They could neither return to the front nor to their homes, and so were sent to psychiatric hospitals. Under the tutelage of another innovative psychiatrist, Michael Foulkes, de Maré was instrumental in helping to develop a methodology to deal with what then was called battle fatigue or shell shock, today called post-traumatic stress.

De Maré was a very fine psychiatrist in working with patients, but given his Marxist view, he also had a deep commitment to using his knowledge of psychiatry to help society heal itself. He adapted the psychiatric technique gained through his war experience into a social change process. David Bohm participated in individual and group therapy with him but also in groups that were de Maré’s experimental median groups, those which were intended to focus on societal issues. De Maré named the methodology they used in the median groups dialogue. So that appears to be where the group process we associate today with David Bohm got its name.

Quite a few people, both patients and non-patients, participated in de Maré’s median groups, and Bohm brought some of his science friends with him. We can credit de Maré with being an individual who, as well as being a psychiatrist, ventured into the application of his skills in the newly emerging field of group therapy and then beyond therapy to social change.

Michael Foulkes

Second in the lineage chain of dialogue was Michael Foulkes September 3, 1898–July 8, 1976), a German-born Freudian psychiatrist. As a young man, Foulkes (né Siegmund Heinrich Fuchs) served in the German army during the First World War, and afterwards, earned a medical degree. Having settled in Frankfurt for postgraduate study, Foulkes became associated with Kurt Goldstein, the founder of Gestalt theory, which shows prominently in Foulkes’ later holistic orientation to psychiatry. Foulkes completed his training in Freudian psychoanalysis in Vienna and, as conditions for Jews became more difficult, he emigrated to England in 1933. As the Second World War ramped up, Foulkes joined the Royal Army Medical Corps, and worked at the Military Neurosis Centre at Northfield where Wilfred Bion and John Rickman had also served as psychiatrists, and it is likely that Foulkes was influenced by them. These three psychiatrists, and others as well, were instrumental in what became known as the Tavistock Group, and they were responsible in developing group methods of treating the battle-fatigued soldiers returning from the World War II battle fronts.

Interestingly, Michael Foulkes had an associate, a Jungian analyst, working with him. For me, that was an interesting find as I often have thought there is much in the dialogic process that is consonant with Jungian thought. I had some communication with the analyst’s daughter and talked about the potential influence of Jung’s concepts on Foulkes.

Finding documentation about Foulkes’ work was difficult. Of course, some of the difficulty was due to his work having been published long enough ago—his first book was published in 1957—for much of it to be out of print. Then, there was the issue of his correct name. Apparently, he is also known as S.H. Foulkes and, during his days in Germany, as Heinrich Fuchs. Thank goodness for Alibris, an online book dealer that specializes in out-of-print books! There are other intrigues that seem to have made tracing this lineage difficult, but I’ll save those for later and just say now that much of the uncovering of the work that took place even before Foulkes and started him on the track of what eventually came to be dialogue, has become available only in the last decade or so. And that is due to the efforts of Italian and Spanish researchers, who suggest that Foulkes had actually ‘borrowed’ initial ideas from another person, then deflected credit to himself11.

Foulkes’ drive was to find a more efficient, effective manner of treating the battle fatigue of the many soldiers returning from war. The then current psychiatric technique was individual therapy, which required several years of treatment. But in the context of thousands of returning shell-shocked soldiers, the psychiatrists couldn’t perform Freudian analysis one-on-one. That would have been impossible in terms of the time treatment would have taken, not to mention the number of psychiatrists who would have been needed. Rather, Foulkes, Bion and Rickman had all, though in different ways, sought to find a way of treatment that would rely on convening a group of patients together to treat individual problems within the group, so we can see the shift that came about when de Maré, as Foulkes’ student, began experimenting with group process as a method of treating societal rather than only individual problems.

Trigant Burrow

So, who is the mysterious person from whom Foulkes allegedly ‘borrowed’ ideas about establishing group therapy? Trigant Burrow (September 7, 1875–May 24, 1950), the first American-born Freudian analyst, completed his training in 1909. Interestingly, when Burrow went to Europe to do his training to become a Freudian analyst, he didn’t go to Vienna where Freud lived but, rather, to Zurich, where he trained with Carl Jung. At that time, Jung and Freud were still working closely, and Jung had taken on much of the role of training others to become Freudian analysts. Again, no wonder dialogue has shades of Jung!

Burrow had been highly trained in biology and experimental psychology, and he retained his laboratory orientation even as he went into psychiatry. He was a researcher who had the unusual capacity to stand back and look afresh at how the human psyche worked. His way of looking anew at the human psyche was much like Bohm’s alternative approach to looking anew at quantum physics. Rather than accepting what was being proposed by Freud and Charcot and others of his time, Burrow wanted to figure out how to directly observe the human psyche in its natural processing as well as to describe how it worked.

In reading about Burrow’s life, one is struck by how similar much of his life experience was to that of David Bohm. Just as Bohm had been excluded from the circle of theoretical physicists at the instigation of Oppenheimer, so too was Burrow ostracized by Freud and his work ignored, even though he was a prolific and innovative researcher and writer. What did he do to invoke the wrath of Freud?

Burrow’s research led him to the conclusion that the human being is by nature a social being, that our primary being is an undivided part of the fabric of the entire human species. We are collective first, individual second. Not only that, he considered that neurosis isn’t primarily an individual malady. Rather, our human society as a whole is neurotic, and thus his term social neurosis. Because neurotic tendencies were learned within a group setting (primarily the family), the way to heal was within a group setting. Both wounding and healing occurred within the group. A related finding was the destructive influence of authority within group settings, so his laboratory process of observing the workings of the psyche was done in groups in which all participants, including himself as the psychiatrist, experienced equity.

Not only were his theories and research findings disturbing to his peers, but they must also have seemed threatening to the status and aura of the profession of psychoanalyst. He challenged the authority assumed by the therapist, claiming that it inhibited the patient from being able to resolve the social images that kept both society and the individual stuck in their neurotic states. Said Burrow:

…what has been for me the crucial revelation of the many years of my analytic work—that, in its individualistic application, the attitude of the psychoanalyst and the attitude of the authoritarian are inseparable12.

The analyst must first do his own serious inner work to repair his relationship between individuality and organismic whole, then enter into the psychoanalytic setting as an equal. Otherwise, what lurked in the unconscious of the psychoanalyst set the limits for a patient’s growth. Here are Burrow’s own words:

The admission that has eventually to be made without qualifying reservation is that the transference upon which we have laid such stress as an objective scientific phenomenon is in truth a state of mind subjectively induced in the patient in direct response to the attitude of unconsciousness on the part of the analyst himself13.

It is no surprise then that Freud didn’t take a shine to Burrow’s research and findings. To Burrow, Freud wrote the following:

Dear Dr Burrow: I would not like you to form an incorrect idea of my position regarding your innovations.… At the present time I do not believe that the analysis of a patient can be conducted in any other way than in the family situation, that is, limited to two people.…I do not believe that we should be grateful to you for the fact that you want to extend our therapeutic task to improving the world.… With my great respect (signed) Freud14.

The words still smoulder with Freud’s anger. Those familiar with Bohm will sense the similarity with Oppenheimer’s attitude, ‘If we cannot disprove Bohm, we must agree to ignore him15.’

Much more can be said regarding the similarities between the lives and careers of these two great researchers and theorists, and in fact will be said later in this presentation. But perhaps this dabbling gives a flavour of their likeness, as well as gives an introduction to the person whom I propose has left the deepest impact on what was to become the initial model of dialogue inherited by Bohm.

One can begin to see some of the threads from which dialogue is woven: the emphasis on wholeness and on the equality of participants (including the facilitator’s); the need for a group setting if healing is to occur; and, the need to rehabilitate the collective. Then, too, the influence of Carl Jung upon Burrow, even if not acknowledged by any of these individuals, begins to shine through, maybe especially in regard to the collective unconscious and more, as we’ll see shortly.

Transition Through the Lineage

This then is the lineage I propose preceded Bohm’s adopting the model and augmenting it with his own ideas. You’ll see that the model shifts as it is handed from one to another up the chain to Bohm. Burrow was a laboratorian at heart. He was trying to discover the manner in which we can look inside the human psyche and observe it directly. He did not propose a practice or therapeutic model. He wasn’t trying to develop a technique to be taught and transferred to others, although many of the processes of his research methodology did transfer to others. Foulkes, different than Burrow, was trying to use the group to provide therapeutic treatment to individuals. De Maré, as well, used the group to treat individuals, but he also went beyond to stretch the newly developing group process as a means of societal improvement. And Bohm, picking up from de Maré, further adapted de Maré’s dialogue for the purpose of social change.

A Few More Steps

One would think this to be the end of the lineage, but not quite. Having become watchful for obscure footnote references that just might have some hints, I ran across a reference to an organization in New York City—the Lifwynn Foundation—founded by Trigant Burrow in the early 1930s. It was still in existence almost seventy years after Burrow’s death. With some digging, I found the Lifwynn Foundation and contacted the president, Dr Lloyd Gilden. Dr Gilden searched through the Foundation’s archives and generously sent me a transcript of parts of the seminar in which Bohm had participated.

Looking further, I found other references to the relationship between David Bohm and the Lifwynn Foundation, which suggest some potentially deep ties. For example, Dr Steven Rosen, a Lifwynn Foundation board member, corresponded with Bohm in the early 1980s regarding Bohm’s concept of ‘proprioception,’ this being the earliest mention I’ve yet found of this often mentioned signature concept of Bohm’s. Also, David Bohm was acquainted with Montague Ullman who was deeply involved in the Lifwynn Foundation. Several Lifwynn Foundation members participated in a New York City dialogue group organized by David Shainberg, a close friend and psychiatrist whom Bohm had met through their mutual relationship with Krishnamurti. And Bohm participated in the Lifwynn Foundation’s conference on addiction in the early 1990s. Interestingly, threads of of Trigant Burrow’s theories had gone full circle and returned to their origination point.

Comparing Aspects of Dialogue

Now what I want to share with you are some of the contributions of these three—Burrow, Foulkes, and de Maré—to the starting model of David Bohm’s dialogue. If you are one who has participated in dialogue, I think that you will recognize these aspects and their correspondences. Of course, these predecessors didn’t all call their processes ‘dialogue,’ but I’m using Bohm’s language in order to provide consistent terminology. In each of the following aspects, I’ll state Bohm’s ideas first to set the context even though he is actually the last in sequence. Here are the aspects we’ll review:

- The Origin of Dialogue

- The Purpose of Dialogue

- Leader/Facilitator

- Sitting in a Circle

- No Agenda

- Thought

- The Collective Nature of Thought/ Fragmentation

- Thought, Prejudices, and Assumptions

- Proprioception of Thought

- Suspension

- The Fix

- The Dialogic Field

- Why Is It So Hard?

- The Outcome

The Origin of Dialogue

Where did dialogue originally come from?

Bohm makes reference to an anthropologist who had lived among a native North American tribe of about fifty people. That tribe periodically met as a whole group, sitting in a circle, talking and talking, though seemingly to no purpose. The conversations occurred without a leader, and everybody participated. The tribal members talked until the conversation just stopped, no decisions having been made. But, through all that conversation, each understood the other and they seemed to know what to do afterwards even though no decisions had been made. Bohm attributes that form of conversing with his ideal of dialogue—a kind of indigenous knowledge about how we’re meant to function as societal entities16.

De Maré said something similar, and perhaps Bohm learned from him. De Maré traced the history of the earliest tribal groups back to over 60,000 years ago, claiming that the early hunter-gatherers throughout the world relied on groups of about thirty or so people for their communal functions. To solve group problems and to deal with their arduous physical situations, the people met, each stating unreservedly just what they felt. Everyone listened, and everyone talked. And then they stopped when the conversation seemed done17 18.

Burrow: We can go back even further by delving into Trigant Burrow’s thoughts, as his starting point for human interaction is more complex and has a major impact on the thinking underlying dialogue. I will begin by quoting Burrow, and then William Galt, one of Burrow’s colleagues:

Man is not an individual. His mentation is not individualistic. He is part of a societal continuum that is the outgrowth of a primary or racial [species] continuum19.

Contrary to our beliefs, our fancies and our cherished suppositions, the individual does not constitute the unit of social motivation and behaviour. The social group, the race or species, is the fundamental unit20.

He means that we first and foremost are part of a phylum or a species. So, contrary to our way of thinking, an individual is like a cell in an organism—a unique part but not a whole. Again, you can see where Freud was disenchanted. So, the social group, the phylum or the species, is the primary unit, with its own inner governance process. To me, this is what we are touching upon with dialogue, into that fundamental social or phylic unit, but it’s also a reality very difficult for us to accept. Burrow claimed that if we really get this, we must reconstruct our identity, recognizing that primarily we are not separate individuals. ‘I’ am an essential part of a ‘we’ and not an entity by myself. That’s tough!

So, we can see that for Burrow, the origin of dialogue is vested in our original identity and communication within the group, from which we are inseparable. It was with us when we began as a species, and it is that to which we strive in consciousness to return.

The Purpose of Dialogue

Why, you might ask, do we do dialogue? What do we expect to achieve?

Bohm’s ideas on why to do dialogue come from various perspectives, but particularly reflect his interactions with Krishnamurti and with de Maré. David Schrum has shared with me the perspective Bohm gained from Krishnamurti. These are David Schrum’s words:

DB dialogue, in its deep purpose, according to Bohm, meets the human holistically; it incorporates all of, what he termed, the three basic dimensions of a human being: the individual, the social, and the cosmic dimensions. Bohm had asked himself of Krishnamurti’s teaching, why, when it was of such depth, was it that it seemed not to have had the intended effect? His answer was, that of the three fundamental dimensions of a human being, the teaching well addressed the individual and cosmic dimensions, but not sufficiently the social dimension. Hence, DB dialogue was born—its generative root—to address the societal element of the human being and to act as a complement to the other factors, which all work together21.

De Maré’s emphasis on the societal level must have seemed to Bohm to fit that niche he felt was missing in Krishnamurti’s orientation. Bohm said that there is much under the surface of our individual or collective consciousness that is dictated by society. We are not even aware of all that is buried under the surface, nor that it dictates our interactions. So, in dialogue we hope to evoke those under-the-surface dictates, to make those things conscious, so that we can then make choices rather than act blindly. Through bringing to the surface these hidden values and intentions, ‘collective learning takes place and…a sense of increased harmony, fellowship and creativity can arise22.’Through dialogue, the societal level is addressed and productive social change may happen. In keeping with the quote shared as we started, ‘People say, “All we really need is love.” If there were universal love, all would go well. But we don’t appear to have it. So, we have to find a way that works23.’Dialogue must have looked to Bohm as ‘a way that works.’

De Maré believed that our basic psychic energy is very raw and unformed. Our human job is to convert it into a form that is usable by the psyche in a productive manner. He called this raw energy hate, and through his dialogue process he hoped to convert this raw hate into respect and participation. So, the basic purpose of dialogue was to convert our unhelpful innate tendencies into productive social process24. In his words,

…dialogue transforms mindlessness into understanding and meaning. Group dialogue works to promote outsight [as opposed to insight] and the expansion of social consciousness, thoughtfulness, and mindfulness25.

It is from dialogue that ideas spring to transform the mindlessness and massification that accompany social oppression, replacing it with higher levels of cultural sensitivity, intelligence, and humanity26.

Foulkes said something entirely different. Whereas Bohm and de Maré said the group fills the gap in the social domain, Foulkes saw the purpose of the group as being only to heal the individual27. He contended most psychological wounding has happened through participation in a group, either in our families or in social groups. Groups hurt, but, paradoxically, the way to heal is in a group context. So, groups have both powers, to hurt and to heal and, of course, his intent was to create the form of group that would provide the context for healing28.

Burrow said that much of what we consider ‘normal’ social interchange is actually neurotic. That false ‘normality’ functions under the surface and creates social images that diverge from the phylic basis of wellbeing. Flushing out those under-the-surface tacit processes that govern our unhealthy behaviour was the constant intent of Burrow’s work. More than that, the purpose was to experience the physical, emotional, feeling aspect of those tacit behavioural directives. By making them conscious within the group circle, individuals could see how unknowingly they had taken on roles and characteristics proscribed by social expectations. Then the individuals would be enabled to learn what truly was born within them, to express themselves from the position of authenticity and true individuality. Then individuals and the group would be coming from the origination point of the human phylum. A return to this domain was humanity’s ultimate destination29 30 31 32.

Leader/Facilitator

Bohm was insistent that there be no leader in an ongoing dialogue group. He did say that when a group begins orienting itself to dialogue that there might need to be a facilitator to help people get the hang of the dialogic process, but very soon that facilitator should meld into the group as one of them33. Now, if you’re working in a corporate setting you’re not going to get very far without a facilitator to guide the conversation, and in most groups we are so accustomed to having a leader that we don’t know how to behave without one. Yet, Bohm clearly said No, it has to be a conversation among equals, and facilitation or leadership has no place in it after the initial group learning. So, you can begin to see that using dialogue as an organizational development technique violates one of Bohm’s essential guidelines. I suggest that when we violate Bohm’s intent by using dialogue in a corporate environment, we also must take into consideration how to make necessary adjustments in order to maintain a coherent process.

Foulkes straddles the fence regarding a facilitator. First of all, he calls the therapist in charge a conductor34 not a facilitator, making an analogy to the conductor of an orchestra. He wants the role of the conductor to be that of a participant, expecting him or her to be equally as vulnerable, but yet keeping much in the background35. At the same time, throughout his career Foulkes remained devoted to Freudian thinking. Perhaps he feared getting on Freud’s bad side as had Burrow. To go as far as to give no role for a psychoanalyst-conductor would have been taking a step too far.

Burrow had had a significant experience early in his career that set his stance regarding equity among group members36. He was treating a young man, using his Freudian analytical process, and this young man became very irritated with Burrow. In essence, he said to Burrow, ‘You assume such an authoritative, arrogant position as you analyse me. I challenge you to switch roles with me.’ Burrow did switch roles with the patient, taking him up on the challenge, and he said it was the most agonizing, humiliating experience he could imagine. What it taught Burrow was the negative impact of authority upon relationships. His sentiment was much like Jung’s, who said, ‘Where love reigns, there is no will to power, and where the will to power is paramount, love is lacking37.’

So, Burrow would say there is to be no facilitator in the group. When he developed his experimental groups, he included people of various roles, his secretary, other therapists, patients, friends, etc. All were expected to take co-responsibility for the way that the process functioned38. This is another way of saying that in situations where authority is involved, we give up our own authority and responsibility and project it onto the one in charge.

Sitting in a Circle

In dialogue, we sit in a circle. That’s one of the hallmarks or basic assumptions of Bohmian dialogue. Where did that come from?

Bohm liked the arrangement of a group sitting in a circle because it both allowed for direct communication and provided spatially for equity of the participants39. Probably he learned this from de Maré, who had learned it from Foulkes.

Foulkes did a great job of describing the circle used in his group process. He said you put the chairs in a circle and have something in the centre as a focal point because people aren’t talking specifically to one other person. Rather,they talk to the whole, and that focal point in the centre encourages the sense of talking to the whole. As a participant, you want to be able to read body language, to see eye movements, to see when someone scoots their chair back, etc. The circle takes away defences that make your implicit communications apparent to all40.

Another important aspect of Foulkes’ work is his description of the meaning of the circle. He mentions various types of circles—magic circles, family circles, wheels, and other metaphors of circles—and he says that there are many implicit meanings that have been projected onto circles over the millennia, meanings that are evoked through the participation in a circle. ‘It has been taken to signify a static compromise, an equilibrium, peripheral movement to and away from the centre. In the language of physics, these are the centripetal and centrifugal tendencies; and in the language of the emotions, an ambivalence of positive and negative (attracting and repelling, loving and hating) forces41.’

Burrow provides a more down-to-earth idea of how the group members are to situate themselves42. He didn’t talk explicitly about sitting in a circle, but rather about sitting around the family kitchen table. Why was that? Well, because that is where most of us begin learning about hierarchy and authority, that is, from our parents as we sit as a family at mealtime. Especially when children are small, much of the initial social training happens around mealtime. That same physical setting seemed to Burrow to be the ideal setting for evoking those patterns learned early on that had become dysfunctional. Many within Burrow’s research group lived in the same facility, and they naturally ate their meals together. So, his research took place at mealtime. The process might be called evoking the beast of the early dysfunctional learning that had occurred in childhood around the family table.

No Agenda

In at least the western world, we focus on goals, objectives, time management, productivity, etc. Why would we want to participate in a meeting without agenda?

Bohm was very intent that we come into dialogue without expectation or predetermined outcome. He said, ‘In a dialogue group we are not going to decide what to do about anything. This is crucial. Otherwise we are not free. We must have an empty space where we are not obliged to do anything, nor to come to any conclusions, nor to say anything or not to say anything. It’s open and free. It’s an empty space43.’

This is Foulkes’ influence, though Bohm likely didn’t recognize it as such. Keep in mind that Foulkes was a Freudian analyst. What would be the setting if you were doing a Freudian analysis? In the early days at least, you would be lying on a couch with your analyst in back of you or at least out of your sight, and you would free associate, letting come to mind and to speech anything that emerged. Why was that? Because the intent was to reach into the unconscious level44 and to give opportunity for issues that are causing difficulties in a patient’s life to surface. In Foulkes’ group therapy setting, it wouldn’t work to have multiple couches in a circle. Besides, he wasn’t wanting to interpret what any one individual was surfacing. What he wanted was to give space for free group association45. He was very careful to not have any kind of agenda or outcome, because he wanted the free interaction46 among group members to evoke things from their unconscious minds, issues most likely to be connected with early family and with individuals’ social groups.

Now, in the dialogue setting I described at the very first, why was it that we began having multiple mental health problems emerge? No doubt our intent of doing dialogue unknowingly crossed the boundary into therapeutic technique intended to delve into the unconscious.

Did David Bohm have awareness of where the prohibition of meeting agenda or outcome originated? Most likely he had experienced such a process in the psychotherapy or sociotherapy groups that de Maré conducted. So far, I’ve not found evidence that he had come in direct contact with Foulkes’ work, but there’s lots yet to learn.

Thought

Quite independently of any of these three individuals whom I have grouped into dialogue’s lineage, Bohm had for decades been curious about the process of thought, and one of his major contributions to the dialogue model he inherited was his deep study of thought. Yet, the overlaps between his thinking and that of these three individuals gives substantiation to my hypothesis of Bohm having started with a model influenced by the three. (And, parenthetically, it is here as well that Bohm’s interaction with Krishnamurti must have had an impact). Here we will delve into those overlaps in just a few of the subtopics that fit in the bigger topic of thought.

The Collective Nature of Thought

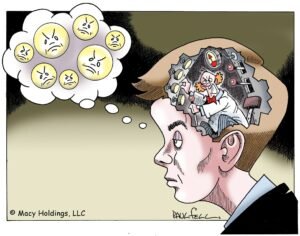

David Bohm’s idea of thought could be imagined to be much like the one in this cartoon picture. Inside of the guy’s head is a little homunculus who manipulates thought, and in this picture the homunculus is in a bad mood. When he pulls certain gears, what comes out of us is bad thoughts. Of course, the homunculus could also pull levers to make good ideas and feelings come out. But, in either case, thoughts are being manipulated rather than being generated by us. In fact, these manipulated thoughts don’t come from just us at all. Rather, they belong to the whole of our family or group or society.

Regarding the collective nature of thought, here’s what Bohm said:

…thought is a system belonging to the whole culture and society, evolving over history…47

A key assumption that we have to question is that our thought is our own individual thought. Now, to some extent it is. We have some independence. But we must look at it more carefully. It’s more subtle than to say it’s individual or it’s not individual. We have to see what thought really is, without presuppositions. What is really going on when we’re thinking? I’m trying to say that most of our thought in its general form is not individual. It originates in the whole culture and it pervades us. We pick it up as children from parents, from friends, from school, from newspapers, from books, and so on. We make a small change in it; we select parts of it which we like, and we may reject other parts. But still, it all comes from that pool. This deep structure of thought, which is the source, the constant source—timeless—is always there48.

We think of ourselves as individuals evolving our own thought. But Bohm is saying that most of our thought is a general form, not individual, and it originates within the whole culture. The structure of thought, which is the constant source, is timeless. So, David Bohm is starting from the same premise as did Trigant Burrow. Thought is a system, and we’re participants in that system.

Burrow: Repeated here from previous pages are Burrow’s descriptions, and you can see the similarity:

Man is not an individual. His mentation is not individualistic. He is part of a societal continuum that is the outgrowth of a primary or racial continuum49,

Contrary to our beliefs, our fancies and our cherished suppositions, the individual does not constitute the unit of social motivation and behaviour.… The social group, the race or species, is the fundamental unit[i].

Perhaps Burrow is the original descriptor of the deep realm of collective thought as it applies to dialogue. At least the two men share a strong resemblance.

Wholeness and Fragmentation

Both Burrow and Bohm, in their own terminology, speak of the whole and its fragmentation, and even though my research evidence hasn’t as yet shown that Bohm actually read Burrow’s work, the overlap in their concepts of wholeness and fragmentation is remarkable.

Bohm pictured that the whole is already there and interconnected but has been torn, so that the continuity of relationships among the many little threads of the whole have been ripped and ruptured. Our job in dialogue is to re-unite these little network links, knitting them back together to repair the whole. Likewise, although we think of ourselves as separate people, Bohm is guiding us toward seeing ourselves as parts of the whole fabric of humanness and seeing our job as reknitting relationships. In this way, we can regain our birthright of wholeness. Of course, we are individuals in the sense that a cell is a part of a whole tissue or organ or body, but our primary essence is dependent upon this whole.

Burrow used quite different terminology, though his concepts were very akin to Bohm’s wholeness and fragmentation. Imagine Burrow in his laboratory observing how the psyche works. Once he began observing things that no one else seemed to have noticed, he didn’t have a vocabulary to name or describe them. So, he made up his own terms. He didn’t, as Bohm did later, speak of wholeness and fragmentation. Rather, he coined new terms: cotention and ditention51. Years prior he had done a PhD in experimental psychology, and his dissertation had been on the topic of attention. So, you can see his extension of that early interest portrayed in his terms cotention and ditention.

Wholeness in Bohm’s terminology was contention in Burrow’s, ‘co’ meaning together, tension together, tension bringing together to create integrity. Ditention, taking the ‘di’ to mean two, refers to a split in tension. In cotention we experience our participation in the whole; in ditention we experience what Bohm called fragmentation. Burrow called this ditentive state partitive52.Things were split off, made to appear separate. He considered the partitive process (which resulted in ditention) to be the source of what he termed social neurosis. He thought it is not the individual who is neurotic, it is society. This ditentive split has become so endemic that society as a whole is neurotic, therefore his term social neurosis53. What happens in the case of someone we consider neurotic or psychotic is that that person is so deeply sensitive to these social forces that they manifest the dysfunction more than most of us do. But all of us participate in the social neurosis.

The complementary nature of Bohm’s and Burrow’s thinking can be seen in how they describe the impact of partitive or fragmentary thinking on ourselves and our society. First, a quote from Burrow, and then one from Lee Nichol describing Bohm’s thinking:

Ditention is a disorder of function that destroys man’s sense of his unity and solidarity as a species and sets each individual or each ideologically amalgamated group or nation against every other individual or nation, as a separate and discrete entity. The private assumption of each of us that he possesses a valid ‘right’ or prerogative and that other people are ‘right’ only in the measure in which they agree with him is concomitant to this ditentive mechanism54.

…the generic thought processes of humanity incline toward perceiving the world in a fragmentary way, ‘breaking things up which are not really separate.’ Such perception, says Bohm, results in a world of nations, economies, religions, value systems, and ‘selves’ that are fundamentally at odds with one another55.

Thought, Prejudices, and Assumptions

Here are the nuts and bolts of the problem.

Bohm considers that assumptions are the key culprits that get us off track. Assumptions are basic to our thoughts and set the definitions about what we think is the meaning of life, what we consider to be our self-interest and our national interest, what our religious values include, and other things that we feel are the bedrock of our lives56. The dysfunction that occurs within both our individual lives and within society is held within those assumptions. We think through our assumptions. We don’t even realize that our assumptions are guiding our thinking and behaviour because they are invisible to us. They are like cookie cutters or lenses through which we look out onto the world, and we regard them as truths57, ever ready to defend them if challenged58. The point of change that needs to happen if we are to come closer to wholeness is at the level of our assumptions.

Burrow says as well that we think with our prejudices. Those are our thinking processes, or, as he would say, ‘prejudice takes the place of thought.… we do not think with our minds but with our prejudices59.’He said something really interesting here. He said prejudices are encysted feeling60. What he means is that the basic issue at fault here is that we have split feeling—both physical and emotional—from thought, whereas they all belong together as one unit. The feelings that are a part of the whole of thought have been forced below the level of consciousness much as on a physiological basis an infection can become encased and cystic. The feeling has no ‘egress61’and festers under the surface of consciousness. Said Burrow, there is going to be no healing of our faulty prejudices if we fail to bring thought and feeling back together. The resolution is to release these feelings from their inner jails. When a person fails to release feeling from that encysted state and thus acts on the basis of prejudice, ‘his reaction is subjective, self-interested and, in the absence of objective grounds of judgement, processes that naturally link organism and environment are no longer operative. Clear, direct judgement has ceased to function62.’

Proprioception of Thought

Burrow and Bohm had very similar concepts of the process of proprioception, i.e., awareness of physical sensation and the location of body within space. As an example of that awareness, we can think of the dramatic physical contortions that members of the Canadian group, Cirque du Soleil, are able to achieve in their performances. What an amazing capacity of proprioception these folks have in order to accomplish their artistic movements. Both Burrow and Bohm stretched that basic physiological meaning of proprioception to include awareness of the movement of thoughts and feelings.

Bohm reasoned that in the case of physiology we can perceive our movement as it happens. Not only that, but we can sense the relationship between intention and action. For example, you want to walk to the mailbox, and then your body takes you there. So, we can see that movement follows intent. Without that connection and awareness of it, we would be unable to maintain ourselves in the world63.Carrying that concept further, Bohm reasoned that the same relationship between intent and movement applies to our thought processes. Here’s how he said it all happens

So, the problem is that the awareness of thought’s intent and movement, not to mention the linkage, is weak or broken, and the result is that we fail to notice the source and interconnections of thought. Bohm held that those hidden thoughts were the repository of our prejudices and destructive attitudes. Were we to become proprioceptive, we would say like the cartoon figure Pogo said years ago, ‘We have met the enemy and he is us64.’

Just as Pogo and Porky Pine are stepping across the trash created by human society, Bohm felt that human thought had been polluted at its source66. Said Bohm, ‘We could say that practically all the problems of the human race are due to the fact that thought is not proprioceptive… The problems we have been discussing [societal issues] are basically all due to this lack of proprioception67.’Our thought is the problem. The way to detoxify thought—and the environment—was to trace thought to its source, and that is why proprioception is such an important capacity.

Burrow’s laboratory for observing how the psyche worked was his workgroup’s kitchen table. As they talked over meals, invariably someone would become irritated about something said. Something got under that person’s skin and s/he was irritable. That person’s job in the moment was to give expression to that feeling, to expand it. Where was that feeling felt in the body? Did it move? Delving deeply into his/her own awareness and experience of such feelings would eventually lead to a memory which was shared with the group, and group members would start to see a similar pattern that they had found in their own life. The sharing led to the awareness that the irritation and its underlying dimensions were really not individual but were in fact communal. Such feelings were part of our common pool of feelings and prejudices, part of our communal heritage. Having that awareness changed the meaning participants made of the original agitation. They ceased blaming others for their own inner reactions. No longer did someone ‘do something to me.’ The projections were called home. Burrow gives a clear description of their purpose and process:

[Our] purpose is to find out, as a group, how the sensations associated with bias and affect-projection feel. That is, what are the sensations associated with making other people and outside events responsible for our feelings (i.e. ‘She makes me mad,’ ‘I’m upset because my train was late,’ etc.)?… What Burrow calls the ‘physiological self’ is immediately accessible to each of us in the proprioceptive sensations and tensions we experience from moment to moment… Through such proprioception, we are learning to become more aware of our own projections and of their power as a motivating factor in human interaction. Our concern is with the development of a fresh approach to social transformation and healing that can be realized on a broad scale… In doing so, contact is made with the energies of the phylic whole68.

Both researchers used the term proprioception, and both related it to the importance of delving into feeling to arrive at the source of thought. Did Bohm learn that concept from Burrow’s work? So far, I have found indications that Bohm was aware of Burrow’s work in 198869. but how that awareness came and if it was the source for Bohm’s usage of the term, I haven’t yet learned.

Suspension

For both Bohm and Burrow, the essential need was for proprioception of thought and its associated feeling. But how did one learn to become proprioceptive? Both suggested a similar process. Bohm called that process suspension.

Bohm might have described suspension like this: When you’re sitting in a dialogue and something comes up for you—an attitude or some irritation—in order to ‘suspend’ your thought you put it out in front of you; you hold it; you don’t act it out; but rather, you become a very deep internal observer of the feelings that are going on. You hold it out so that you can see it as if you are looking at it in a mirror. You let it develop in a way that enables you to trace its feeling back in your memory to something that had gotten stuck and rancid. The group becomes a set of mirrors in the circle, reflecting you back to yourself. Perhaps you had shared your opinion on the topic being discussed, and someone in the circle frowns, or someone backs their chair up, or someone smiles. All of those responses are feedback about you and to you. The dialogue circle offers a whole group of reflectors around you to help you go inside and delve into the unnoticed feelings underlying your irritated assumption or belief or attitude. In sharing with the group about one’s inner delving in this manner, other participants recognize similar feelings, and, in time, Bohm says, ‘…you can see that everybody’s in the same boat70.’

Burrow: Bohm’s description of suspension sounds much like Burrow’s description of proprioception a few paragraphs back. As Burrow searched for a methodology of directly observing the psyche, a major find had come from learning how to connect into one’s inner feelings. Burrow describes that find as shifting one’s point of observation, metaphorically moving back as if to put one’s affects or feelings out in front of oneself. For example, if anger (or jealousy, or love, or greed) were the primary sensation coming up for an individual during a group session, then the individual would imagine that anger in front while remaining perceptive to the overall sensations occurring in the body as a whole. The affect of anger would be in the foreground, the overall bodily sensations in the background. This splitting of sensations with a foreground and a background produced impactful results. Burrow believed that what they had tapped into was the projection (a significant psychological process) of social images that originated within mankind as a whole and which came from the unproductive and unconscious habits of thought passed down from generation to generation, within all societies. Those social images were the ‘autopathic preoccupations’ that gave birth to prejudice and social neurosis71.

Thought and Its Fix

What is the essential process that allows us to mend our mistaken thought processes and makes individual and societal healing possible? Whether in a dialogue circle or in an individual setting, the process is the same.

Bohm believed that the process of fixing what ails us requires proprioceptive thought and suspension, as has been described in previous paragraphs. Much of his description of those processes infers that they are to happen within a dialogue setting. But Lee Nichol, a close associate of Bohm, offered additional information in an article entitled ‘Wholeness Regained—Revisiting Bohm’s Dialogue72.’ In that article, Nichol quoted Bohm as saying, ‘I think people are not doing enough work on their own, apart from the dialogue groups,’ and Nichol then proposed the antidote Bohm would have prescribed.

Nichol’s first suggestion has to do with things that fit into our sense of ‘me,’ that is, the ego, our assumptions, our self-image, our world-image, etc. Bohm had talked about these in his descriptions of proprioceptive thought and suspension, but Nichol extends Bohm’s intent here to include what he called ‘the most basic assumption of all—the assumption of the solidity and primacy of the ego.’ Here he refers to what we had called earlier the homunculus. We need to go directly into that most basic assumption, questioning the ‘existence and veracity of the ego,’ and ‘questioning the questioner.’ Doing so, ‘it may be possible to enter into a genuinely new order of insight.’

Nichol also delves into Bohm’s thinking about the role of the body in the suspension process. By paying attention to the body’s highly sensitive reactions to things that disturb our self-image and provoke our emotions, we have an immediate and accurate indicator. When provoked, if we can harness our cognitive responses—hold our thoughts steady—and then at the same time let our physiological responses come into awareness—then a different picture of the outward situation is likely to appear. We see beyond our assumptions. Said Nichol, ‘One effect of giving attention to the body is thus to bring our conscious awareness more closely in line with what is actually occurring.’ We see a contrast between what our usual assumption-based response would be and what our inner feeling has shown us, leading us to the awareness that the ego, that homunculus pulling the levers in our minds, is not the whole story. Then, says Nichol, the ‘deep cultural conditioning is turned on its head: awareness is now seen as primary; thoughts flow from awareness, and the ego, far from being a “real thing,” is merely a reflexive display resulting from ingrained thought patterns.’

Foulkes and de Maré took a stance which shows up in Bohm’s conception of the dialogue group but less in the individual description as provided by Lee Nichol. Both psychiatrists, particularly Foulkes, who was trained in Gestalt theory, saw the individual as embedded within a context of relationships—individual and group being inseparably part of one whole. Individuals were nodal points within a total group network, not entities unto themselves73. The group comes first and takes precedence over the individual. According to Foulkes, ‘What stands in need of explanation is not the existence of groups but the existence of individuals74.’ Looking back over recorded history and imagining what occurred before recorded history, he concluded that the development of individuality is very young and superficial75.

Foulkes presented a paradox: It is groups that wound and hurt us, but it is groups that heal us. Of course, groups differ in their healthiness and thus their impact. It’s the healthy groups which have that capacity to work through the wounds. Foulkes professed, ‘That which heals is the sense of belonging, of participation, of being respected, of being an effective member of a group, of being able to share and participate, and of feeling a part of constructive experiences of life76.’To heal is to experience ‘sympathy, love, affinity, liking, interest, and attraction77,’ to be supported and accepted, and to be listened to even when one’s expression is yet inarticulate and unpolished78, to be able to talk and be listened to, to share with others, to see that one is living through experiences much like others, to be able to express one’s loneliness and isolation79. The composite of those descriptors sounds like Bohm’s intention for a dialogue group!

Foulkes summarized his orientation in what he called the cardinal rule. ‘There’s a reciprocal need to understand and to be understood80. And that then was the very core of what it takes to heal: to understand and to be understood. It takes both. And, here again, we can see some of the influence that carried from Foulkes through de Maré to dialogue, through Bohm’s emphasis on the listening to and the understanding of others’ comments.

Burrow was intent on differentiating his research findings from the predominant idea that thinking was the basis of healthy adaptation. The dominant clue, he said, lies not in pondering or talking about the mental images of a troublesome81 situation that are projected, but rather in concentrating on the sensations within the body.

But, mind you, one is not thinking… One acquired an internal appreciation of tensions internal to the organism, and observations are based solely upon the internal sense or sensation of these tensions. And so, one’s research is now not in the field of thought where all that he has known as research has hitherto lain. The research of the student of phylobiology is within the naked sensation or his own phylobiology—the organism of man82.

Change and healing, then, come not through thought. He said we can’t think about healing, we have to do healing. It takes being in the moment, being sensitive enough that we can feel our emotions, becoming adept at perceiving the immediate ‘naked’ sensation within our body. We must become competent at investigating our own inner-organic process83 and able to reattach the sensations of thinking and feeling. From the contrast between the socially normal mode of adaptation and the proprioceptive inward sensing mode, the individual was provided with ‘the requisite fulcrum for overthrowing the wishfully superimposed dominance of the socially insular84.

So closely aligned are the thinking of Bohm and Burrow that one must wonder whether David Bohm had had contact with Burrow’s work.

The Dialogic Field

If you’ve participated in dialogue, then you’ve probably heard about the dialogue circle as being described as a container. That term is frequently used in dialogue work, and at least one source of it comes from Carl Jung’s metaphor of alchemy and the psyche. Hundreds of years back, alchemists put earth—basic dirt—and a particular liquid into a vessel, and then the vessel was plugged up by a stopper, making a tight seal. Next, the vessel was put over a flame so that the liquid inside was heated and the vapours would rise up, condense, drip back to the bottom. This process would repeat over and over again until the contents had transformed into the metaphorical gold. That is a story, in psychological thinking, explaining allegorically the relationship between therapist and patient, and it’s also the metaphor for what happens in a dialogue circle. The dialogic container is a safe circle that holds everything that comes forth, that transforms it into a new meaning. And more, the container refers to a particular energy field that develops through the interactions of the dialogue group members.

Here in Pari, where we are right now, David Peat considered this town to be a container for the various people who gathered with the intent of stretching their understanding and consciousness. Even the circular shape of this town, he said, is suggestive of the container.

Bohm instructed us to sit in a circle, and as we dialogue, an impersonal feeling can develop, a sense of relationship. Rather than being based on friendship, the relationship he sought didn’t depend upon knowing each other, but rather upon ‘mutual participation85’ in meaningful conversation. In his words, ‘…if we can really communicate, then we will have fellowship, participation, friendship, and love, growing and growing. That would be the way86.’

In his mind, the participation would create a high energy of coherence that would go beyond the original intent of dialogue to solve societal problems. The field he envisioned was indeed extensive. ‘And perhaps in dialogue, where we have this very high energy of coherence…it could make a new change in the individual and change in the relation to the cosmic. Such an energy has been called “communion.” It is a kind of participation…. The idea of partaking of the whole and taking part in it; not merely the whole group, but the whole87.’ He called that sense of relationship that occurs in the dialogic container Koinonia88.

Patrick de Maré had taught Bohm the term, Koinonia—a word that comes from the Greek Orthodox Church. Said de Maré, ‘It refers to the atmosphere of impersonal fellowship rather than personal friendship, of spiritual-com-human participation in which people can speak, hear, see, and think freely, a form of togetherness and amity that brings a pooling of resources89. As well, de Maré had been taught about the formation that occurred in their group therapy process of what Foulkes had termed, the matrix, a term that overlaps with de Maré’s Koinonia.

Foulkes and de Maré both felt that it was the matrix that gives voice to people. Foulkes had observed that as his patients participated in his therapeutic circles, there was a point when the group gelled, so to speak. Something very different seemed to occur in these sessions, actually something that was present from the very first get-together of a new group and provided a subtle but palpable orientation and direction. Foulkes described what he was observing: ‘They speak now through one mouth, now through another. Active currents within the group may be expressed or come to a head in one particular person, between particular persons, or may, in a sense, be ‘personified’ in individuals. But whatever is going on in the group is always regarded by us as a process developing in this total group90.’ Apparently the matrix—or container—has a mind of its own, expressed through the voices and behaviours of the individuals. It was an entity with autonomy and intention.

All of that sounds very mystical. Let me give you an example from a dialogue group I conducted recently. In that group was an attorney, a very clear-minded, process-oriented attorney. In the midst of a deep dialogue the group was at an impasse, stuck. Of all the people there, he was the one I least would have expected to speak in the midst of an uncomfortable silence. ‘I have no idea why I’m saying what I’m going to say, but….’ And then he blurted out something entirely beyond his usual mode of thought. In fact, had he been using his thought, he probably wouldn’t have said it! But, it was just what the group needed to break the ‘stuckness’ and to take understanding to a deeper level. It was the spur. Now that happens frequently in a dialogue, there is something that emerges from the group that no one person can credit themselves for, an emergent idea that comes out of the process of the whole. So that’s what Foulkes is describing as the matrix.

According to Foulkes, such happenings occur when the matrix has been evoked. What is the matrix? The word matrix comes from Latin for mater, or mother91. Think back to my assertion in the first part of this presentation regarding the implicit impact of Carl Jung on dialogue. Carl Jung wrote about the deep impact of the maternal archetype. What Foulkes is suggesting is that the dialogic field is an artifact of the maternal archetype. Now, if you look over there at the drawings that David Schrum used yesterday, what side of the brain would you say dialogue falls on? David well described what is going on in the brain during a dialogue. The right side of the brain is considered by many researchers to be the side that is holistic and more ‘feminine’ in its processing, whereas the left side of the brain is more logical and ‘masculine’ in its processing.

Commenting on how the sides of the brain participate in dialogue, David Schrum suggested: ‘Maybe you could say it this way: both sides are definitely involved, but the right side has primacy. The same is true of other creative processes—it starts in the right and is articulated in the left.’

Burrow said as well that the common mind field in which we all participate has its basis in the feminine, in mothering. Briefly, his analogy would be that in the last trimester of pregnancy particularly, the foetus is developing a sense of consciousness, but it’s not consciousness of individuality. Rather, it’s consciousness of participating in the maternal matrix, and that, then, is the essential foundation of commonality on which we base everything from then on. Here are his words:

Man is not an individual. His mentation is not individualistic. He is part of a societal continuum that is the outgrowth of a primary or racial continuum. As the individual finds his basis in an individual continuum with a maternal source, so the social organism has its basis in a continuum with a phylogenetic matrix. It is my thesis that this racial continuum is the basis of man’s societal life92.

De Maré, Foulkes and Burrow are saying that the sense of wholeness has its basis in the maternal archetype and earliest notions of being a part of the mother-infant unity. At that point, one is totally immersed in the maternal. We always have the deep urge to recreate wholeness, to regain that from which we were separated in our earliest days. It is that energy field of oneness that we crave and that all the researchers found that we could re-experience in the safety of the circle, whether we call it by the name of dialogue, Koinonia, matrix, container or by some other name.

Why Is It So Hard?