Your cart is currently empty!

Jung on Evil

the March 2020 issue of Pari Perspectives.

Introduction

We need more understanding of human nature, because the only real danger that exists is man himself. He is the great danger, and we are pitifully unaware of it. We know nothing of man, far too little. His psyche should be studied, because we are the origin of all coming evil.

(Jung 1977: 436)

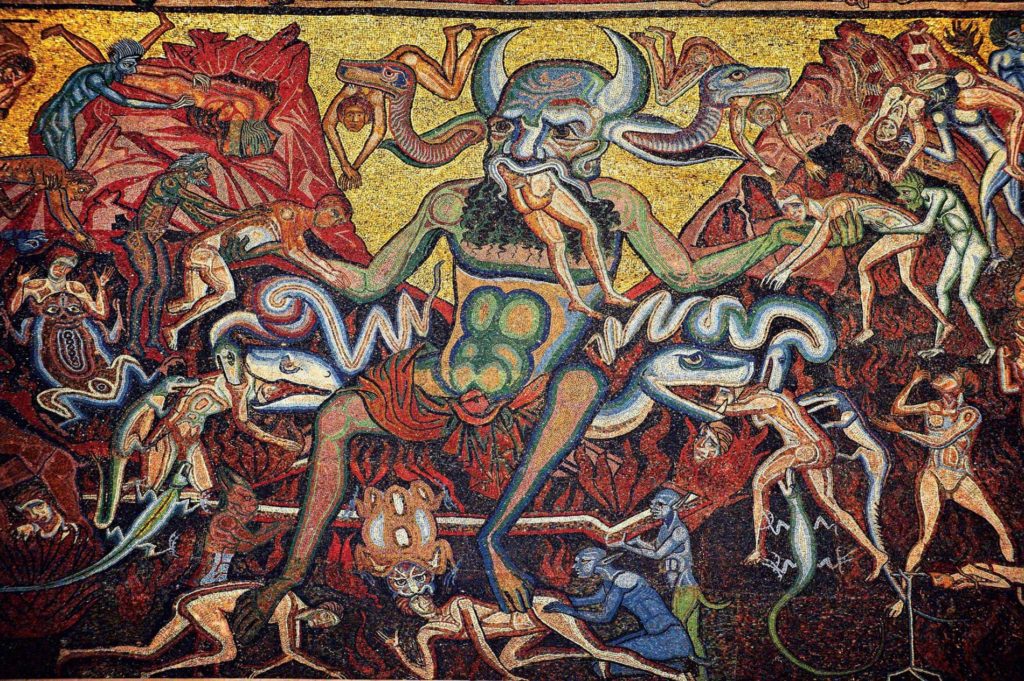

The problem of evil is a perennial one. Theodicies abound throughout history, explaining God’s purposes in tolerating evil and allowing it to exist. Mythological and theological dualisms try to explain evil by asserting its metaphysical status and grounding and the eternal conflict between evil and good. More psychological theories locate evil and in humanity and psychopathology. Probably humans have forever wrestled with questions like these: Who is responsible for evil? Where does evil come from? Why does evil exist? Or they have denied its reality in the hope, perhaps, of diminishing its force in human affairs.

The fact of evil’s existence and discussions about it have certainly not been absent from our own century. In fact, one could argue that despite all the technical progress of the last several thousand years, moral progress has been absent, and that, if anything, evil is a greater problem in the twentieth century than in most. Certainly all serious thinkers of this century have had to consider the problem of evil, and in some sense it could be considered the dominant historical and intellectual theme of our now fast closing century.

More than most other intellectual giants of this century, Jung confronted the problem of evil in his daily work as a practicing psychiatrist and in his many published writings. He wrote a great deal about evil, even if not systematically or especially consistently. The theme of evil is heavily larded throughout the entire body of his works, and particularly so in the major pieces of his later years. A constant preoccupation that would not leave him alone, the subject of evil intrudes again and again into his writings, formal and informal. In this sense, he was truly a man of this century.

As indicated in the quotation given above, which occurs in his famous BBC interview with John Freeman in 1959, two years before he died, Jung was passionately concerned with the survival of the human race. This depended, in his view, upon grasping more firmly the human potential for evil and destruction. No topic could be more relevant or crucial for modern men and women to engage and understand.

While Jung wrote a great deal about evil, it would be deceptive to try to make him look more systematic and consistent on this than he actually was. His published writings, which include nineteen volumes of the Collected Works (hereafter referred to as CW), the three volumes of letters, the four volumes of seminars, the autobiography Memories, Dreams, Reflections, the collection of interviews and casual writings in C. G. Jung Speaking, reveal a rich complexity of reflections on the subject of evil. To straighten the thoughts out and try to make a tight theory out of them would be not only deceptive but foolhardy and contrary to the spirit of Jung’s work as a whole.

While it is true that Jung says many things about evil, and that what he says is not always consistent with what he has already said elsewhere or will say later, it is also the case that he returns to several key concerns and themes time and time again. There is consistency in his choice of themes, and there is also considerable consistency in what he says about each theme. It is only when one tries to put it all together that contradictions and paradoxes appear and threaten to unravel the vision as a whole. We may agree with Henry Thoreau that consistency is the hobgoblin of small minds, but it is still necessary to register the exact nature of these contradictions in order understand Jung’s fundamental position. For he does take a position on evil. That is to say, he offers more than a methodology for studying the phenomenology of evil. He actually puts forward views on the subject of evil that show that he came to several conclusions about it.

It is also extremely important to understand what sorts of positions he was trying to avoid or to challenge. In doing so he may have fallen into logical inconsistency in order to retain a larger integrity. To approach Jung’s understanding of the problem of evil, I will ask four basic questions. In addressing them, I will, I hope, cover in a fashion all of his major points and concerns. By considering these questions I will cover the ground necessary to come to an understanding of Jung’s main positions and to appreciate the most salient features of his conclusions. In the order taken up, these questions are:

1 Is the unconscious evil?

2 What is the source of evil?

3 What is the relation between good and evil?

4 How should human beings deal with evil?

These questions represent intellectual territory that Jung returns to repeatedly in his writings. The first is a question he had to grapple with because of his profession, psychiatry, and his early interest in investigating and working with the unconscious. The other three questions are familiar to all who have tried to think seriously about the subject of evil, be they intellectuals, politicians, or just plain folk whose fate has brought them up against the hard reality of evil.

Is the Unconscious Evil?

Jung spent much of his adult life investigating the bewildering contents and tempestuous energies of the unconscious mind. Among his earliest studies as a psychological researcher were his empirical investigations of the complexes (cf. Jung 1973), which he conceived of as energized and structured mental nuclei that reside beneath the threshold of conscious will and perception. The complexes interfere with intentionality, and they often trip up the best laid plans of noble and base individuals and groups alike. One wants to offer a compliment and instead comes out with an insult. One does one’s best to put an injury to one’s self-esteem behind one and forget it, only to find that one has inadvertently paid back the insult with interest. The law of an eye for an eye and a tooth for a tooth (the talion law) seems to remain in control despite our best conscious efforts and intentions. Compulsions drive humans to do that which they would not do and not to do that which they would, to paraphrase St Paul.

The unconscious complexes appear to have wills of their own, which do not easily conform to the desires of the conscious person. Jung quickly exploited the obvious relation of these findings to psychopathology. With the theory of complexes, he could explain phenomena of mental illness that many others had observed but could only describe and categorize without understanding. These were Jung’s first major discoveries about the unconscious, and they formed the intellectual basis for his relationship with Freud, who had made some startlingly similar observations about the unconscious. Later in his researches and efforts to understand the psychic make-up of the severely disturbed patients in his care, Jung came upon even larger, more primitive, and deeper forces and structures of the psyche that can act like psychic magnets and pull the conscious mind into their orbits. These he named archetypes. They are distinguished from complexes by their innateness, their universality, and their impersonal nature. These, together with the instinct groups, make up the most basic and primitive elements of the psyche and constitute the sources of psychic energy.

Like the instincts, which Freud was investigating in his analysis of the vicissitudes of the sexual drive in the psychic life of the individual, the archetypes can overcome and possess people and create in them obsessions, compulsions, and psychotic states. Jung would call such mental states by their traditional term, ‘states of possession.’ An idea or image from the unconscious takes over the individual’s ego and conscious identity and creates a psychotic inflation or depression, which leads to temporary or chronic insanity. The fantasies and visions of Miss Miller, which formed the basis for Jung’s treatise, The Symbols and Transformations of Libido published in 1912-13 (later revised and published as Symbols of Transformation in CW), offered a case in point. Here was a young woman being literally driven mad by her unconscious fantasies.

On the other hand, however, Jung was at times also caught up in a more romantic view of the unconscious as the repository of what he called, in a letter to Freud, the ‘holiness of an animal’ (McGuire 1974: 294, see below). Freudian psychoanalysis promised to allow people to overcome inhibitions and repressions that had been created by religion and society, and thus to dismantle the complicated network of artificial barriers to the joy of living that inhibited so many modern people. Through analytic treatment the individual would be released from these constraints of civilization and once again be able to enjoy the blessings of natural instinctual life. The cultural task that Jung envisaged for psychoanalysis was to transform the dominant religion of the West, Christianity, into a more life-affirming program of action. ‘I imagine a far finer and more comprehensive task for psychoanalysis than alliance with an ethical fraternity,’ he wrote Freud, sounding more than a little like Nietzsche.

I think we must give it time to infiltrate into people from many centres, to revivify among intellectuals a feeling for symbol and myth, ever so gently to transform Christ back into the soothsaying god of the vine, which he was, and in this way to absorb those ecstatic instinctual forces of Christianity for the one purpose of making the cult and the sacred myth what they once were—a drunken feast of joy where man regained the ethos and holiness of an animal

(McGuire 1974: 294)

So, while the contents of the unconscious—the complexes and archetypal images and instinct groups—can and do disturb consciousness and even in some cases lead to serious chronic mental illnesses, the release of the unconscious through undoing repression can also lead to psychological transformation and the affirmation of life. At least this is what Jung thought in 1910, when he wrote down these reflections as a young man of thirty-five and sent them to Freud, his senior and mentor who was, however, a good bit less optimistic and enthusiastic about the unconscious.

In its early years, psychoanalysis had not yet sorted out the contents of the unconscious, nor had culture sorted out its view of what psychoanalysis was all about and what it was proposing. Would this novel medical technique lift the lid on a Pandora’s box of human pathology and release a new flood of misery into the world? Would it lead to sexual license in all social strata by analyzing away the inhibitions that keep fathers from raping their daughters and mothers from seducing their sons? Would returning Christ to a god of the vine, in the spirit of Dionysus, lead to a religion that encouraged drunkenness and accepted alcoholism as a fine feature of the godly? What could one expect if one delved deeply into the unconscious and unleashed the forces hidden away and trapped there? Perhaps this would turn out to be a major new contributor to the ghastly amount of evil already loose in the world rather than what it purported to be, a remedy for human ills. Such were some of the anxieties about psychoanalysis in its early days at the turn of the century. Is the unconscious good or evil? This was a basic question for the early psychoanalysts. Freud’s later theory proposed an answer to the question of the nature of the unconscious—good or evil?—by viewing it as fundamentally driven by two instincts, Eros and Thanatos, the pleasure drive and the death wish. These summarized all unconscious motives for Freud, and of these the second could be considered destructive and therefore evil. Melanie Klein would follow Freud in this two-instinct theory and assign such emotions as innate envy to the death instinct. Eros, on the other hand, was not seen as essentially destructive, even if the drive’s fulfillment might sometimes lead to destruction ‘accidentally,’ as in Romeo and Juliet for instance. From this Freudian theorizing it was not far to the over-simplification which holds that the id (i.e. the Freudian unconscious) is essentially made up of sex and aggression. Certainly from a Puritanical viewpoint this would look like a witch’s brew out of which nothing much but evil could possibly come. The id had to be repressed and sublimated in order to make life tolerable and civil life possible. Philip Rieff would (much later) extol the superego and the civic value of repression!

(Jung 1975: 311)

This is a view often expressed in Jung’s writings. Yet evil is an essential adjective, an absolutely necessary category of human thought. Human consciousness cannot function qua human without utilizing this category of thought. But as a category of thought, evil is not a product of nature, psychical or physical or metaphysical; it is a product of consciousness. In a sense, evil comes into being only when someone makes the judgement that some act or thought is evil. Until that point, there exists only the ‘raw fact’ and the pre-ethical perception of it.

Jung discusses the issue of types of ‘levels’ of consciousness briefly in his essay on the spirit Mercurius (Alchemical Studies, CW 13, paras 247-8). At the most primitive level, which he calls participation mystique, using the terminology of the French anthropologist Levi-Bruhl, subject and object are wed in such a way that experience is possible but not any form of judgement about it. There is no distinction between an object and the psychic material a person is investing in it. At this level, for instance, there is an atrocity and there is one’s participation in it, but there is no judgement about it one way or another. For the primitive, Jung says, the tree and the spirit of the tree are one and the same, object and psyche are wed. This is raw, unreflective experience, practically not yet even conscious, certainly not reflectively so. At the next stage of consciousness, a distinction can be made between subject and object, but there is still no moral judgement. Here the psychic aspect of an experience becomes somewhat separated from the event itself. A person feels some distance now from the event of an atrocity, say, and has some objectivity about the feelings and thoughts involved in it. It is possible to describe the event as separate from one’s involvement in it and to begin digesting it. The psychic content is still strongly associated with an object but is no longer identical with it. At this stage, Jung writes, the spirit lives in the tree but is no longer at one with it.

At the third stage, consciousness becomes capable of making a judgement about the psychic content. Here a person is able to find his or her participation in the atrocity reprehensible, or, conversely, morally defensible for certain reasons. Now, Jung writes, the spirit who lives in the tree is seen as a good spirit or a bad one. Here the possibility of evil enters the picture for the first time. At this stage of consciousness, we meet Adam and Eve wearing fig leaves, having achieved the knowledge of good and evil.

In early development, the first stage of consciousness is experienced by the infant as unity between self and mother. In this experience the actual mother and the projection of the mother archetype join seamlessly and become one thing. In the second stage, the developing child can make a distinction between the image of the mother and the mother herself and can retain an image even in the absence of the actual person. There is a dawning awareness that image and object are not the same. A gap opens up between subject and object. The infant can imagine the mother differently than she turns out to be when she arrives. In the third stage, the child can think of the mother, or of the mother’s parts, as good or bad. The ‘bad mother’ or the ‘bad breast’ does not suddenly begin to exist at that point, but a judgement about her behaviour (she is absent, for instance) is registered and acted upon. Now the possibility of badness (i.e. evil) has entered the world.

This view of evil—that it is a judgement of consciousness, that it is a necessary category of thought, and that human consciousness depends upon having this category for its on-going functioning—generates many further important implications. One of them is that when this category of conscious discrimination is applied to the self, it creates a psychological entity that Jung named the ‘shadow.’ The shadow is a portion of the natural whole self that the ego calls bad, or evil, for reasons of shame, social pressure, family and societal attitudes about certain aspects of human nature, etc. Those aspects of the self that fall under this rubric are subjected to an ego-defensive operation that either suppresses them or represses them if suppression is unsuccessful. In short, one hides the shadow away and tries to become and remain unconscious of it. It is shameful and embarrassing. Jung provides a striking illustration of discovering a piece of his own shadow in his account of traveling to Tunisia for the first time. From this experience he extracts the observation that the rationalistic European finds much that is human alien to him, and he prides himself on this without realizing that his rationality is won at the expense of his vitality, and that the primitive part of his personality is consequently condemned to a more or less underground existence.

(Jung 1961:245)

It is this piece of personality that the cultivated European typically bottles up in the shadow and condemns violently when it is located in others. The magnificent film Passage to India depicts such projection of shadow qualities with exquisite precision. Jung would experience the full force of shadow unawareness and projection in the Nazi period and in World War Two. Because the human psyche is capable of projecting parts of itself into the environment and experiencing them as though they were percepts, the judgement that something is evil is psychologically problematic. The stand-point of the judge is all-important: Is the one making a judgement of evil perceiving clearly and without projection, or is the judge’s perception clouded by personal interest and projection-enhanced spectacles? Since evil is a category of thought and conscious discernment, it can be misused, and in the hands of a relatively unconscious or unscrupulous person it can itself become the cause of ethical problems. Is the judge corrupt, or evil? This would require another judgement to be made by someone else, and this judgement could in turn be the subject of yet another judgement, ad infinitum. There is no Archimedean vertex from which a final, absolute judgement on good and evil can be made.

Despite staking out his ground here, which could easily lead to utter moral relativism, Jung did not move in that direction. Just because the categories of good and evil are the product and tool of consciousness does not mean that they are arbitrary and can be assigned to actions, persons, or parts of persons without heavy consequence. Ego discrimination is an essential aspect of adaptation and consequently is vital to survival itself. Ego consciousness must take responsibility for assigning such categories of judgement as good and evil accurately or they will lose their adaptive function. If the ego discriminates incorrectly for very long, reality will exact a high price. In order for consciousness to perform its function of moral discrimination adaptively and accurately, it must increase awareness of personal and collective shadow motivations, take back projections to the maximum extent possible, and test for validity. Time and time again Jung cries out for people to recognize their shadow parts. Questions of morals and ethics must become the subject of serious debate, of inner and outer consideration and argument, and of continual refinement. The conscious struggle to come to a moral decision is for Jung the prerequisite for what he calls ethics, the action of the whole person, the self. If this work is left undone, the individual and society as a whole will suffer.

As opposed to a theorist who would root the reality of good and evil in metaphysical nature itself and then rely on inspiration, intuition, or revelation to decide upon what is actually good and what is evil, Jung puts forward a theory that places the burden for making this judgement squarely upon ego consciousness itself. To be ethical is work, and it is the essential human task. Human beings cannot look ‘above’ for what is right and wrong, good and evil; we must struggle with these questions and recognize that, while there are no clear answers, it is still crucial to continue probing further and refining our judgements more precisely. This is an endless process of moral reflection. And the price for getting it wrong can be catastrophic. Because Jung considered this to be perhaps the central human task, he ventured even into the risky project of making such judgements about God Himself. Is God good or evil, or both? These are questions that Jung addresses in his impassioned engagement with the Biblical tradition, and especially in his late work Answer to Job.

To ask if God is good or evil, or both, is for Jung the equivalent of asking this question about the nature of reality. Is reality good? Yes. Is it evil? Yes. In Jung’s view the criminal remains a member of the human community and represents an aspect of everyone. Those traits one condemns in the perpetrator also belong to oneself, albeit usually in a less blatant form.

One of the goals of a personal psychological analysis is, in Jung’s view, to make an inventory of psychic contents that includes shadow material. Once this is done and the shadow is acknowledged and felt as an inner fact of one’s own personality, there is less chance of projection and greater likelihood that perception and judgement will be accurate. This does not eliminate making judgements about evil, for this category remains in consciousness as a tool for discriminating reality, but it does allow for less impulsive and emotionally charged, blind attribution of evil in cases where serious ambiguity exists. Still, if evil is an adjective, applied by ego consciousness to actions and events in the course of discriminating and judging reality, this fails to explain the source of the behaviour, the acts, and the thoughts that are judged to be evil. What is the source of the deed, the ‘raw fact,’ which one judges to be evil?

For example, war is a common human event that is often judged to be evil. Is war-making native to the human species? It would seem that war-making is intrinsic to part of human nature. There are mythological figures, both male and female, who represent the spirit of war and the human enthusiasm for it. Human beings seem to have a kind of aggressiveness toward one another and a tendency to seek domination over others, as well as a strong desire to protect their own possessions and families or their tribal integrity, which added together lead inevitably to conflict and to war. Some would say that war is a natural condition of humanity as a species, and it would be hard to dispute this from the historical record. Is making war not archetypal? Does this not mean that evil is deeply woven into the fabric of human existence? It is one thing to say that the tendency to go to war is endemic in human affairs, however, and another to say that evil is therefore also a part of human nature. War is an event, and each instance of it must be evaluated by consciousness in order to be condemned as evil. Conscious reflection upon warfare has found that some wars are evil and others not, or that some wars are more evil than others. Theologians have elaborated a theory of the just war. In itself war can be considered morally neutral, a tool that can be used for good or evil. So while it may be claimed that the source of the behaviour that will later be condemned as evil is an inherent part of human nature, this still does not mean that evil is archetypal.

What is the source of evil?

Going deeper, though, can we frame the question more precisely to tease out those aspects of human behaviour that are universally condemned as evil and ask if they are inherent in human existence? Can it be shown that human beings naturally and inevitably commit acts that would universally be judged as evil? And if so, how are we to understand the source of these acts? How does the evil deed happen? For we know that evil does occur throughout human history and experience.

Jung’s own major confrontation with evil on a large scale was Nazi Germany. Much that the Nazis did individually and collectively has been judged as evil. Jung was close enough to the center of this political phenomenon to observe it unfolding right before his eyes, to feel its energy and to know its threat personally. He was fascinated by the mythic dimensions of German Nazism and for a time by its energy. In the early 1930s he wrote things that show he believed that the collective unconscious in Germany was pregnant with a new future. Perhaps, he thought, some good could come out of it, perhaps the unconscious was giving birth to a new era that would lead humanity forward. Mercurius is ambiguous, and the products of the creative unconscious are sometimes bizarre in their first appearance. Jung most definitely underestimated at first the Nazis’ potential for evil. What he did observe by the mid-1930s, however, was a sort of collective psychosis taking hold in Germany, a society-wide state of psychic possession.

In his essay on Wotan (CW 10, paras 371-99) he writes of this phenomenon. An archetypal image from ancient Germanic religion and myth, Wotan was stirring again in the German soul, and this was generating martial enthusiasm and battle-frenzy throughout the population. Wotan was a war god, and the German people were now showing the signs of irrational possession by battle-eagerness that is seen in warriors preparing for battle. This state of possession was disturbing normal ego consciousness among the Germans and their sympathizers to the point of clouding normal moral judgement. Under these conditions the psyche is ripe for releasing behaviour that is primitive, irrationally driven, and highly charged with affect and emotion. Jung predicted that the German people were getting ready to act out a Wotanic possession. What had brought this archetypal constellation into historical reality? The enactment of the Wotanic fury in modern Germany needs to be explained by referring to historical events and patterns: Germany’s humiliation after World War One, the national degradation and political and economic turmoil of the 1920s, the compensatory politics of arrogance and revenge espoused by the Nazi leaders and bought wholesale by the populace. The appearance of the Wotan archetype in the collective consciousness of the German nation could be interpreted as a psychological compensation for a national mood of humiliation and loss of self-worth, the archetypal basis for a sort of narcissistic rage reaction.

In Jung’s psychological theory, the regression of psychic energy to primitive levels of the collective unconscious constellates a compensatory archetypal symbol, which galvanizes the will and brings about a new flow of energy into the system, along with a strong sense of meaning and purpose. But this is also often accompanied by ego inflation and identifícation with primitive energies and impulses. What is created is a ‘mana personality’ (cf. ‘Two essays on analytical psychology’, CW 1, paras 374ff.). There are no guarantees that what this archetypal symbol and its derivative notions and energies stand for will bear careful ethical scrutiny and inquiry. The crusader spirit of someone identified with archetypal thoughts and values will argue fiercely that the ends justify the means and will overlook all countervailing considerations. This person may look like a moral leader when in fact what is being espoused is an abdication of moral reflection. The crusader for liberation or equality or moral rearmament may well be advocating at the same time abaissement du niveau mental.

A strong influx of archetypal energy and content from the unconscious shades the light of ego consciousness and interferes with a person’s ability to make moral distinctions. Now ordinary moral categories and the ego’s ethical attainments are easily over-ridden in the name of ‘higher’ (certainly stronger) values. And when these dubious higher values have become the group norm, individual and collective shadows have found a secure playground. This is how evil is unleashed on a mass scale; it is individual shadow added to shadow and then raised to the square power by group consensus, permission and pressure.

Under conditions like this, which held sway in Germany and other Nazi-dominated areas of Europe between 1933 and 1945), kinds of behaviour that would ordinarily be suppressed and repressed become acceptable. Indeed acts like betrayal of friends, robbery of personal property, lying and cheating and public humiliation of others, which would normally be condemned in civil society, may suddenly become praiseworthy. Now it is allowed and indeed encouraged to murder neighbours, to plunder their property, to rape their women, to take revenge for past slights and present envies. Even if some level of discipline remains in the ranks on the collective level, there is a strong incentive to look aside when individuals are ‘carried away’ with enthusiasm for the cause or lose control of themselves. Thoughts and actions that were formerly condemned as evil are now condoned or overlooked.

The inflation produced by ideology and propaganda-inspired images creates a collective abaissement du niveau mentalsuch that ego consciousness loses its ability to make considered moral judgements. The normal functioning of a personal conscience is interrupted. Everyone is swept up in the emotions of the moment, and the air is filled with urgent promptings onward. It is the rare individual who retains a personal sense of good and evil and continues to hear the voice of conscience in the midst of a collective state of possession and archetypal inflation.

The source of what we perceive as evil, then, is a mixture of psychological content (the shadow) and psychological dynamics that allow for, encourage, or require shadow enactments. This is different from saying that the shadow is evil per se. What is in the shadow may well, under certain conditions, be seen as good and useful for promoting human life and well-being. Sexuality and aggression are cases in point. Any archetypal image and any instinctual drive may yield evil action under psychological conditions of inflation and identification with primitive archetypal contents accompanied by social conditions of permission or secrecy. Used under other conditions and governed by more favorable attitudes, these same psychological contents and drives can yield benefit and goodness. The question becomes, then, what inspires their deployment for evil? Is there something in the human psyche that can lead one consistently to choose evil over good?

In his reflections on Western religious history in Aion (CW 9/2), published in the aftermath of the Second World War in 1951, Jung interprets the history of Christianity with reference to the astrological sign of the Fishes. In this Platonic Year (the ‘aion’ of Pisces), which has lasted for two thousand years, there has been an underlying theme of conflict between great opposing forces, which is symbolized in astrology by two fish swimming in opposite directions. As Jung delineates this history, he sees the conflict as raging between spirituality and materialism (spirit vs. body) and a parallel conflict between good and evil. These have been interwoven with the conflict between masculine (as spirit) and feminine (as materia) figures and values.

The ego is drawn by the magnetism of God’s need to incarnate His own dark destructiveness. This is the ultimate source of evil, its absolute home. It was this horrifying thought that inspired Jung to write Answer to Job and to recognize, in Aion (1951), that ‘it is quite within the bounds of possibility for a man to recognize the relative evil of his nature, but it is a rare and shattering experience for him to gaze into the face of absolute evil’ (para 19).

Doubtless there is a logical contradiction in Jung’s wanting to say both that evil is adjectival and the product of conscious human judgement on the one hand, and that the persistent presence of evil in the world is due to God, who is trying to incarnate some part of His divine nature in time and space, on the other. To this challenge 1 am sure Jung would answer that evil is a paradox. Like the nature of light, if you look at it one way it appears to be a wave, something in the mind of the beholder; if you look at it the other way, it appears to be a particle, something emanating from the ontological ground of being. Both are true, and both are needed ‘in order to attain full paradoxicality and hence psychological validity’(Alchemical Studies, CW 2, para 256) and to give an adequate account of the phenomenon of evil.

What is the Relation Between Good and Evil?

What horrified Jung most was, by all accounts, irrevocable splitting. Perhaps this was rooted in his fear of madness (cf. Jung 1961: 170ff), or in his early childhood experience of strife between his mother and father. At times Jung fell victim of the dark fear that he might be so internally split that he could never find healing and would forever suffer from a psychic Amfortas wound. Whatever the personal motivation may have been, his whole psychology and psychotherapy were aimed at overcoming divisions and splits in the mind and at healing sundered psyches into operational wholes.Wholeness is the master concept of Jung’s life and work, his personal myth.

Thus when it comes to discussing the relation of good and evil it is altogether consistent that Jung should oppose dualism at any cost. This was for him the worst possible way of conceiving of the relation of good and evil, to pit one against the other in eternal and irreconcilable hostility. At bottom good and evil must be united, both derivative from a single source and ultimately reconciled in and by that source. For Jung a dualistic theology would have been anathema, a dualistic psychology harmful.

Never one to shy away from using mythological or theological language, Jung would therefore strongly entertain the notion that good and evil both derive from God, that one represents God’s right hand, so to speak, and the other His left. In the Biblical account of Job, Jung found confirmation of this view. Here Satan belongs to Yahweh’s court. Jung sees him as Yahweh’s own dark suspicious thought about his servant Job. In the New Testament, good and evil would become more harshly polarized in the images of Christ and Antichrist, but always Jung would refer Satan and Antichrist back to Lucifer, the light-bringer and the elder brother of Christ, both of them sons of Yahweh. From the other angle of vision, both good and evil are products of conscious judgement. This is as true of good as it is of evil (cf. above). Moreover, at this level of consideration, good needs evil in order to exist at all. Each comes into being by contrast with the other. Without the judgement of evil there could be no judgement of good, and vice versa. Good and evil make up a pair of contrasting discriminations that is used by ego consciousness to differentiate experience. A complete conscious account of any situation or person must include some employment of this category of good-and-evil if it is to be a fully differentiated account.

Jung’s insistence that one cannot have good without evil was a thorny point of contention between him and his theologically minded friends. Theologically educated students of Jung’s psychology, such as the Dominican Father Victor White, would take strong exception to this view. For them it was not inconceivable to postulate the existence of absolute goodness without evil, since this is after all the standard Christian doctrine of God. Good does not require evil in order to subsist any more than light needs darkness in order to exist. But for Jung this was highly debatable. Pure light without any resistence or darkness could not be seen, and therefore it would not exist for human consciousness. Since he looked upon good and evil as judgements of ego consciousness, it would be impossible in his view for real persons to name such a thing as light or goodness if they had never experienced darkness or evil.

Because Jung was basing himself on a psychological view of evil—i.e. that it is a judgement of consciousness—there were endless misunderstandings with philosophers and theologians who wanted to think about the nature of evil in non-psychological terms. This could have been clarified easily enough if Jung had not also wanted to maintain the other end of the paradox about evil, that it is rooted in God’s nature, in the nature of reality itself. At this end of the discussion Jung would put forward a theory of opposites: psychic reality is made up of ordered patterns that can be spread out into spectra of polarities and tensions like good-to-evil and male-to-female. Without the energic tensions between the poles within entities like instinct groups and archetypes, there would be no movement of energy within the relatively closed system of mind/body wholeness. It is the tension within these polarities that yields dynamic movement, the fluctuations of libido in the psychic system. Jung argued that the same is true of the flow of energy in physical systems.

Evil within the psychological realm is equivalent to entropy in the physical realm: it is the tendency within a system to run down and to disintegrate, a flow of energy toward destruction. Good, by contrast, is equivalent to negentropy, the flow of energy in the opposite direction, toward building systems up into greater levels of integration and complexity. Both forces are at work in the psyche and in nature, and both are needed to produce the kind of reality we know in life and study in science. Like Whitehead, Jung saw reality as a process, an interplay of forces in a dynamic and constant stream of activity that build up and dissolve structures. Remove any force or tension in this process, and you have a different system and probably one that does not work as well or at all.

At this somewhat conspicuously metaphysical level of speculation, Jung would affirm that good and evil need each other in order for either one to exist at all. It is not here only a question of conscious discernment and judgement but a question of reality. Psychic and physical and spiritual life as we know them can best be described as constant flux, continuous transformation and change, perpetual movement. Nothing stands still for very long. And this restlessness is generated by the tensions within and among opposites such as good and evil. Structures arise and dissolve in endless transformations, as the forces congealed in their organizations allow themselves to be contained for a time and then move on. This perception and conviction on Jung’s part helps to account for his extraordinary fascination with alchemy and its account of the continuous transformation of elements.

How Should Human Beings Deal With Evil?

Jung was critical of moral crusaders, Albert Schweitzer being a case in point (cf. ‘Flying saucers: A Modern Myth of Things Seen in the Sky,‘ CW 10, para. 783). He felt that people who become too identified with a particular cause or moral position inevitably fall into blindness regarding their own shadows. Would Schweitzer consider the shadow of his mission to the Africans? Jung was doubtful.

The first duty of the ethically-minded person is, from Jung’s psychological perspective, to become as conscious as possible of his or her own shadow. The shadow is made up of the personality’s tendencies, motives, and traits that a person considers shameful for one reason or another and seeks to suppress or actually represses unconsciously. If they are repressed, they are unconscious and are projected into others. When this happens, there is usually strong moral indignation and the groundwork is laid for a moral crusade. Filled with righteous indignation, persons can attack others for perceiving in them what is unconscious shadow in themselves, and a holy war ensues. This is worse than tilting at windmills, and it ends up being morally reprehensible in its own right.

A careful examination of conscience and of the personal unconscious is therefore the first requirement if one seeks seriously to do something about the problem of evil. This self–examination is itself an exercise in moral awareness. To see one’s own shadow clearly and to admit its reality requires considerable moral strength in the individual. It also requires the prior attainment of moral consciousness, of the ego’s ability to make moral discriminations. This is not a given. There are individuals who do not reach this level of development, and there are in each of us as well areas of unconsciousness that function in a similarly blind fashion when it comes to questions of good and evil. The capacity to make ethical judgements and the willingness to make them about oneself as well as others are prerequisites for further moral action.

Even leaving aside serious psychopathology, i.e. psychotic and debilitating neurotic conditions, the human being has a great capacity for self-deception and denial of shadow aspects. Even persons who are otherwise giants from a moral point of view can have gaping lacunae of character in certain areas. Religious and political leaders who become famous for their far-reaching moral vision and ethical sensitivity are often known to fall into the hole of acting out instinctual (for example, sexual) strivings and desires without much apparent awareness of the moral issues involved. Their acting-out may be conveniently compartmentalized and hidden away from their otherwise scrupulous moral awareness.

For the psychopath or sociopath Jung would recommend attempting to raise the level of conscious functioning to the moral level. Whether or not this is possible after a certain age has been attained or a certain level of commitment to a hardened counter-position has been made are open questions. It may well be the case that if moral conscience is not cultivated in the early years of development there is little likelihood that it will ever manifest in a fashion other than as compliance. Learning the language of moral discrimination may be a lot like learning other languages: after the age of thirteen or so it becomes increasingly difficult to learn them very well, and eventually for some it may be impossible altogether. One must begin moral education at an early age.

With respect to others who are more or less normally developed to a level of moral discrimination, further shadow realization is a matter of applying consciousness and discrimination to sectors of experience that have been walled off. These sectors generally have to do with the instinct clusters: eating, sexual behaviour, addictions to activity, to reflection, or to creativity. Wherever human behaviour becomes driven by unconscious needs, desires, or wishes, shadow gathers and usually remains unexamined. The missionary who destroys one culture in order to create another, the political prophet who cannot stay away from prostitutes, the feminist who suffers from an eating disorder are all familiar examples.

As a psychologist and a psychotherapist of individuals, Jung would begin addressing the practical question of what to do about evil by confronting the individual with his or her own shadow parts and areas of underdevelopment of consciousness. After this work has been started, the psychological task would become one of integrating the shadow. Integration is a term that refers to a process different from differentiation but not its opposite. Differentiation has to do with making distinctions and becoming conscious of differences, the differences between good and evil for example. Integration is a term that refers to the psychological act of ownership: that is myself! With respect to integration of the shadow, and of the evil that it contains, this means that the evil of which I was formerly unaware in myself (and probably found in someone else, a projection-carrier) I now can locate within. Moral awareness is brought to bear upon an area of attitude, thought, or behaviour that had before lain in darkness.

Sometimes a whole culture will suddenly make a shift and begin looking in a new moral light at behaviour that had easily passed as acceptable or harmless only a short time earlier. Sexual harassment in the work-place is one such area in recent times. The sexually explicit invitation or comment, the off-colour joke or insinuation, the casual hug or pat are now suddenly regarded with a kind of moral awareness that would have been considered prudish or in bad taste only a few years ago. This is more than a change in taste and social personas: it is an expansion of moral consciousness into new territory. Suddenly the boss who grabs is not someone to be humoured but someone to be prosecuted.

Obviously such moral discriminations as these can fall into the hands of unscrupulous individuals who will unethically take up a cause or make a charge for reasons of personal gain or advancement. The secretary who is about to be fired for incompetence and a poor work attitude cries foul on grounds of sexual harassment in order to forestall her unemployment. This does not mean that the advance in collective moral awareness is a mistake, but only that less morally developed individuals can always find a way to use situations to their own advantage.

Society cannot bear the full responsibility for moral consciousness or the lack of it, however. For Jung, the emphasis always returns to the individual. Rules and laws may be passed with the intention of legislating moral behaviour and eradicating evil from the social system as far as possible, but moral education must still be aimed at the individual. For an unscrupulous individual can always use the system to evil ends. A good tool in the wrong hands is a dangerous weapon, was a concept often expressed by Jung. Yet, too, from his experience with Nazi Germany, Jung would have to confront the shadow within the larger structures of society. The ways in which a society is set up, through its laws and customs, has a lot to do with how evil is handled and perceived within its precincts. ‘Moral man and immoral society,’ a concept of Reinhold Niebuhr’s, would not have been foreign to Jung’s consciousness after World War Two. Many scrupulous and well-intentioned individuals within theThird Reich ended up serving the Devil by being good and obedient citizens.

There is Jung’s work a strong appreciation of collective shadow as well as individual shadow. Once the work of shadow awareness and integration has been to a large extent done by the individual, therefore, the work of confronting evil and dealing with it continues, but in the wider area of society and politics. Jung was not a quietist about evil in the larger world, in politics, in economics, or on the stage of world affairs. Perhaps his Swiss upbringing and citizenship played a role in moving him toward a position of neutrality with regard to intervening in other people’s affairs, but Jung was no pacifist with regard to confronting the evils of totalitarianism. He feared, perhaps wrongly, Communism more than Fascism in the Europe of the 1930s, and his anti-Communist and anti-Stalinist feelings were strong and often stated. He felt deeply that fanatical ideologies of any sort were demonic because they depended for their existence upon identification with archetypal images and upon grandiose inflations, which crippled individual accountability and destroyed moral consciousness. Such ideologies should therefore be confronted by psychological interpretation, which would have the benefit, if successful, of restoring consciousness to its proper human dimensions. The ideologue depends on drawing archetypal projections to himself from the populace, which in turn robs the populace of its authority and certainly robs individuals of their integrity as ethical human beings.

In principle, then, Jung would advocate a form of political activism that would bring psychological interpretation to bear upon collective human affairs. This would be to carry a version of psychotherapy out of the clinical setting into the world.

Jung himself began this kind of work, applying his psychological theory and hermeneutic to history and Western culture, in the last several decades of his life. He became, in effect, the psychotherapist of Christianity in his voluminous writings on its history, theology, and symbols (cf. Stein 1985), and in his other numerous writings about culture, art, and modernity he addressed the ills of the age. In this fashion he was engaging the issue of evil in the world at large.

Because of his view of the inevitable presence of shadow in human affairs, Jung could in the final analysis by no means be considered a utopian or a social idealist. ‘Every bowl of soup has a hair in it,’ was a favorite Swiss aphorism of his. Reality, God, as well as the human individual have shadow wrapped tightly into the warp and woof of their very being, and there is no means to remove it surgically. While it is important for consciousness to throw its weight on the side of good, of life, of growth and integration, it must be recognized that this is a struggle without hope for final victory. For victory would be stasis and so would spell defeat anyway from the point of view of evolution. The evolution of reality depends upon the dynamic interplay of forces that we call good and evil, and where the evolution of consciousness and spirit is finally headed is still beyond our knowledge. The best we can do is to participate in this unfolding with the greatest possible extent of consciousness. Beyond that we must reconcile ourselves to leaving the outcome up to the Power that is greater than ourselves.

References

Jung, C.G. (1953-83) The Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Eds. H. Read, M. Fordham & G. Adler, trans. by R.F.C. Hull, London: Routledge, and Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—— (1975) Letters, Vol. 2, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

—— (1977) C.G. Jung Speaking: Interviews and Encounters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

McGuire, W. (ed.) (1974) The Freud-Jung Letters. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stein, M. (l985) Jung’s Treatment of Christianity: The Psychotherapy of a Religious Tradition. Wilmette, IL: Chiron Publications.