Your cart is currently empty!

Inescapable Journeys: On Integrating the Dual and Non-dual

the September 2021 issue of Pari Perspectives.

God to Death:

Go thou to Everyman,

And show him in my name

A pilgrimage he must on him take,

Which he in no wise may escape

The Sumonyng of Everyman (1510)

Many in Europe still remember the experience of living under totalitarian regimes; the rest of us have had the good fortune to experience nothing but post-WWII and post-Cold War peace, security and prosperity. We may all well wonder at the collapse of the events industry, the closure of arts venues and the Balkanisation of our hallowed university culture over the past year-and-a-half. Historical memory may help us both recall what life can really be like when orthodoxies of any kind are allowed to set the pace, and reflect on the fact that any form of totalitarianism is the result of a process not dissimilar to what we are witnessing today. Yet there is an opportunity here, too: as individuals we find ourselves questioning aspects of experience that, pre-pandemic, would not have warranted a moment’s consideration. Although much current debate may prove futile or misguided in the long-run, there is the possibility that a greater sensitivity for what is crudely termed ‘otherness’ may take hold, namely a sensitivity towards not only other cultures and histories, but also other dimensions of sentience.

This essay is not about validating what are widely considered to be conspiracy theories, or speculating about who has what agenda and why. It is a statement about the experience of being an individual human being and the need to steward that every bit as much as the need to steward this beautiful blue planet, which, more than our home, is our amniotic sac.

The question of duality and non-duality goes to the heart of our experience. It is essentially a question about whether we shall be able to find the right reasons for making wise choices instead of settling for a compromised outlook in which we feel unbeholden to any higher sense of who we are and what we are worth. As individuals we can value our differences regardless of nationality, gender, ethnicity, creed or religion, or whatever other constituency we find ourselves belonging to, and yet still recognise ourselves as integral to a whole that belongs to us as much as we belong to it. Hannah Arendt captures this essential paradox in Ich selbst, auch ich tanze, where she explodes the limitations of a dualistic worldview in which the observer is kept from the ‘sheerness’ of experience by dint of a single-minded focus on an act of measurement:

Unermessbar, Weite, nur,

Wenn wir zu messen trachten,

Was zu fassen unser Herz hier ward bestellt1.

Immeasurable, vastness, only

When we strive to measure

What our hearts have been called upon here to grasp

The trap of dualism is to believe it can do without the non-dual when in truth they need each other. Much as we try, we cannot properly measure the universe, yet we are called to become present to it, to live the experience of it, and to allow ourselves to be humbled by it. We may be minuscular on the grand scale of things, but measurement alone cannot help us in our understanding here. Human experience of the universe can be as infinite as the universe itself, because the two are not separate from one another.

There is no boundary between outer and inner, no substantive difference between the experience and the object: the ‘hier’ in Arendt’s stanza suggests a ‘dort’ as well, a ‘there,’ and by mentioning one we imply the other. ‘Hier’ there is the responsibility of this particular life that we are called upon to live, but ‘dort’ there is the true understanding of the nature of things. That is where we learn that our actions today have consequences tomorrow. That is where we learn that we can’t simply alter the script because it suits us in this particular moment in time. It is there that we are reminded that we are part of something vast and miraculous, but also that to be a part of that takes a sense of responsibility that has precious little to do with much of what we see in the news today; that the lack of perfection, the failure to match the standard, is not itself a crime. We may be called to account for it, but we must not be cancelled because of it, because that would be to perpetuate the cycle of violence, retribution and ignorance. ‘Hier’ and ‘dort’ are opposite ends of a Heraclitean riddle: the road is one and the same; what changes is our direction of travel, and therefore how we experience it.

I. The Calling

An early sixteenth-century English morality play, The Somonyng of Everyman (1510, unattributed), presents a God displeased by human sinfulness who calls upon Death to summon Everyman to a pilgrimage ‘which he in no wise may escape.’ Everyman’s dilemma, which is our dilemma, is how to approach the one inescapable journey that makes us all pilgrims with a common purpose. The figure in the play is an archetype of human vice: wealthy and profligate, but also insensitive to the consequences of his actions. He is the objective correlative of a journey that takes us from an atomised, essentially passive worldview to a realisation of wholeness and salvation, from a dual to a non-dual view of existence. As we shall see, the play’s virtue as a parable is that it tells the oldest and most common story of all, a story which can be re-enacted in all sorts of narratives; its drawback, one that is however fully in keeping with its historical context, is that it does not fully do justice to the question of the agency of the human person.

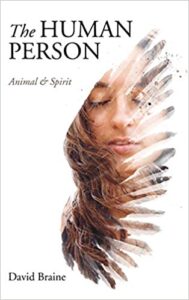

In his 1992 book, The Human Person: Animal and Spirit, the late British analytical philosopher and Catholic theologian, David Braine, writes:

We have here a perspective within which at root human beings as deliberators or even contemplators are external to what they administer so that they can regard it in a purely technical way, whether the ends they seek are pleasurable sensations or pleasurable inner biographies or some subjectively chosen external end or complex of ends. We may call this the technological mentality. This becomes the mentality which subordinates human beings’ environment and even their own bodies to whatever some ideology may project as in the human interest and which relegates the theoretical and contemplative aspect of human nature to the area of play and recreation except in so far as they may have some utilitarian by-product geared to human beings’ temporarily imagined interests2.

Braine laments the split in philosophical thinking brought about by Descartes and culminating in Sartrean angst over the lack of a good reason for choosing one course of action over another. The dualist split essentially robs us of the ability to see any good reason why we should not abuse our bodies or the environment, or why we should spend any time at all thinking about what will happen when we reach the end of our separate journeys. Like many of Chaucer’s pilgrims, we are too busy with lusty gossip about who slept with whom and not taking the time to reflect on why we are riding to Canterbury.

Braine views the philosophical world as divided between views shaped by language, experience or each person’s condition on the one hand, and the perspective that physical science is entirely sufficient and adequate for explaining everything as material process, and therefore untroubled by subjective sensibilities, on the other. The power of the materialist argument derives in part from the sheer scale of the physical universe and its high degree of describability at many different physical levels3, in view of which it just seems simpler to class the human and the biological as a local epiphenomenon rooted in an unconcerned vastness of physically observable phenomena. Materialism in this view is the result of a kind of awestruck abdication from subjective pretensions. But without the subjective experience of the individual there can be no observation at all.

In Braine’s view it is more problematic to give an account to humans of humans than it is of God. He often expressed frustration at how the philosophers used technical jargon in one way, while linguists, psycholinguistics, mathematicians, physicists and biologists all used the same or similar jargons each in their own creative ways, and he made it a focus in his life’s work to reconcile the various disciplines to one another in such a way that different academic departments could at least communicate with each other and understand what was being said to them by colleagues in other departments. The result, published in 2014, is the third part in a three-volume series which constitutes his magnum opus: Time, Reality, and the Existence of God (1988), The Human Person: Animal and Spirit (1992) and Human Understanding: The Roots of Creativity in Speech and Thought (2014). The latter of the three works alone is the result of twenty-one years of labour. It is a monumental synthesis of knowledge, bridging language, psychology and science, and it is held together with a profound love of the human experience and a desire to bring about a holistic view embracing existence in its entirety, from the biological to the metaphysical.

We might say that such a holistic view becomes possible when we, like Everyman, answer our final calling and become true pilgrims at last, accepting that no worldly attachment can prepare us for the final call. The religious orthodoxy of the Everyman allegory may jar secular sensibilities, yet the concerns it voices are every bit as real today as they were five hundred and eleven years ago; perhaps even more so as we continue to reap the benefits of a dualist, materialist vision of life on earth that feeds on amnesia about our past and ignorance about our present and future.

II. The Undiscovered Self

In such a perspective, the soul, when it is seen at all, is viewed as something separate from the body and therefore unconcerned with or by the cause-and-effect outcomes of actions in this life. A recent WEF white paper, published in August 2020, ‘Human Capital as an Asset: An Accounting Framework to Reset the Value of Talent in the New World of Work,’ estimates that a company’s intangible assets, including human capital and culture, account for an average of 52% of a company’s market value. Yet although chairs and CEOs acknowledge the need to integrate human capital metrics with financial and operational measurements, it is argued that the management frameworks needed to achieve this integration are still lacking. The direction of travel is clear, therefore.

The well-being of the individual is being optimised in an effort to put such frameworks in place. Those of us who grew up in a pre-digital world, where the private space of the mind was still private, the flu jab was still a personal choice and the body was still one’s own to inhabit, risk finding ourselves, as the cliché goes, on the wrong side of history. No amount of mindfulness workshops or poetry seminars will ever redeem the entropic burden of a corporate value-system geared to the maximisation of profit and growth, and the relentless acquisition of influence that drives it. To all appearances, the individual is cared and catered for; in reality, it is just a byte in a database engineered to safeguard a bottom-line-without-kindness4. The person contained within this data system still has to face Everyman’s inescapable journey alone, and one can only wonder whether the experience of being atomised, commodified and transmogrified into corporate capital shall ever yield the basic safeguards that avert revolutions.

The individual, writes C.G. Jung in his 1957 book The Undiscovered Self, here seen as an irrational datum that cannot be clearly defined or reduced to a statistical system, is the true and authentic carrier of reality. If you count all the pebbles on a beach, he reasons, you can calculate an average size of pebble and thereby establish a ‘norm’ against which to measure each individual. The result is that when you look for the pebbles on your beach that conform perfectly to your norm, you may well find yourself frustrated by the sheer idiosyncrasy of each individual pebble. A doctor needs the abstract model as an aid to understanding, but the real skill consists in dealing with the person before them. The perspective that is needed, therefore, is one in which the abstract, statistically-based model is made to serve the needs of individual sentience. I refer to it when I need to understand patterns on a scale larger than that of individual existence because it can be useful to calculate the probability ratios of something occurring or not occurring. But that is only one part of my task: the rest is translating the translation into the appropriate idiolect so that the recipient of the information can use it efficiently. Extraction and translation are both required for knowledge to be shaped into a reliable framework that does not require ideology to plaster over conceptual holes in the thinking.

A particularly acute observer of the twentieth century, Jung was understandably anxious about the dangers of massification exemplified in his own time by National Socialism and Communism. His concerns are still germane. If he could estimate, as a clinician, that for every ‘insane’ person he treated, there must have been ten at least wandering about streets barely even aware they had a problem, today we really have to reflect, as we wander about the streets, on whether it’s even possible to conceive of a human being who has spent even just a handful of years in this world and has not been the victim of some kind of abuse or trauma. And if we can accept that even levels of trauma that would not trigger the sceptic in the reader are far more widespread than it has generally been the custom to acknowledge, we have to ask ourselves how this actually plays out in society and what impact its neglect is having on the course of our history as a civilisation. None of this can be addressed with corporate well-being metrics: the only viable route is the inward journey to the undiscovered self unmediated by the generalisations of corporate, medical or religious orthodoxies.

It is often argued that focussing on the individual breeds narcissism, a view that is often encountered particularly in certain responses in orthodox circles to the rise in recent decades of what is dismissively labelled as ‘New Ageism’5. There is no question that it is not enough to seek the undiscovered self. The journey is not complete unless we integrate what we learn with our experience as relational creatures. And therein lies the rub. How to renegotiate this integration of dual and non-dual?

Braine once said to me that the existence of God is a simple matter of reasoning; the real mystery is the Incarnation. In other words, the very nature of the relationship between the two sides of this coin we call Life is mysterious. This implies that it is probably best explored through manifestations rather than definitions. One example is the question of scale, as suggested by Arendt in the stanza quoted earlier. The individual is generally assumed to be the minimum countable unit in a society, and the problem has always been how to fit large numbers of such units into an overarching vision of the world. Operating on a case-by-case basis is seen to be ineffectual in the extreme. Hence the logistical efficiencies of the German military machine during WWII, identified by some as the blueprint for modern corporate organisational culture6.

Nothing could be more emblematic of the unsustainability of such a model for the individual human being than the German concentration camp. The camp system was supported by a bureaucratic infrastructure that translated people into numbers, thereby robbing them of the dignity, hope and meaning that are essential for the human person to thrive on a scale which is appropriate to them. This was true for the prisoners, of course; but also for German citizens caught up in the machine of horror whether they supported it or not, for instance the station masters noting down the numbers of the trains passing through their stations, or the stenographers diligently recording each and every utterance and cry of the tortured prisoners7. The unsustainability of the model is illustrated even by much well-intentioned environmental journalism. Reports on the ‘global’ situation frequently cite numbers and statistics that are far beyond the capacity for a single human to process in anything like a meaningful way, and sure enough one of the primary causes of activist burnout is the sense of overwhelm brought on by the enormous scale of the problems we are facing.

Everyman’s crimes are universal in their gravity, but God’s answer is to summon us to a reckoning that is intensely personal. As an allegorical figure representing the whole of humanity, Everyman is at the same time a gendered person with a particular life-story7. Like Everyman, we are both universal and particular, and this is where our focus can perhaps regain a sense of balance. It is only when we have been abandoned by family, friends and fortune, and are left stripped naked before the prospect of facing the last leg of our life-journey alone, that we finally discover how to reintegrate our individual existence into the universal truth of life. This is a homecoming we all seek because it is what makes us essentially human.

III. The Flower Sermon

Everyman is not given to introspective agency, however. In the Christian view, God has to intervene to lead Everyman back to the righteous path. In other, non-Abrahamic traditions, the journey itself is what we have because the transcendental lives in all beings, and that crucial first step towards realisation is an awakening in the private experience of the individual.

When I have dreams that are worth recording, I write them down in the dark on a notepad I keep close by. I write by touch alone, often with my eyes still closed. The result is how I imagine my writing will be when I am old and infirm: a gangly, clumsy scrawl that struggles with order and is barely legible the following morning. Usually, however, it is comprehensible enough for me to record it after I get up. Recently, I wrote:

P. takes me on a spacewalk and teaches me how to survive without atmosphere by not breathing in. I learn a subtle form of inner transition between out breath and breathing in, and I learn quickly. I start observing things from this new perspective, so close, so on the edge between my own death and this extraordinary way of seeing things differently, so close to something completely revolutionary, yet so simple to enact. It just takes a great sense of responsibility.

I can still feel in my body the crushing proximity of the death that awaits me should I succumb to the instinct to try and suck air into my lungs in the usual physical manner. I am alive and present to my experience as a human being in a way that turns fear into vital energy, but it is only through the development of a sense of responsibility that this teaching becomes accessible to me. And the teaching itself happens without words.

There have been a number of experiences of silent transmission in my life, and in fact I would say it happens to all of us. There was the young, orange-robed monk meditating in Hyde Park in Sydney in 1995; an older orange-robed monk standing by a waterfall on the island of Kho Pha Ngan in Thailand a few months later; and some years after that, at an aikido seminar in Italy, a moment of meditative silence held by the teacher, at that time a trainee in the Burmese Mahasi tradition in Myanmar. Generally speaking, such experiences cannot be forgotten; but there are some that happen beyond the bounds of memory. These help shape the very signature of our life. In a non-metaphorical sense, they set our course for the span of years we have on this Earth. The one I wish I could remember, the memory I don’t have because I was too small at the time to remember it now, was told to me by my sister.

It was 1976, in the second year of my life. At the time I was living with my family in a place called Navicello. Navicello, now like then, is barely more than an old bridge over a rambunctious river with a few brick farmhouses dotted among the orchards. If you go to Navicello expecting to find a somewhere, you would be disappointed. It’s the kind of place where your guide suddenly stops in the middle of nowhere and says: “We are here.” The perfect place for a young pilgrim to start out. The only difference between then and now is that in 1976, ‘in the quiet of the world, where there was less noise and more green,’ there was much, much less traffic, especially of the heavy kind. Until well into the twentieth century, the area was a malarial flood plain between two sizeable rivers, and to this day there are people there who coexist with a particular type of anaemia inherited from malaria-stricken ancestors. The earth is fertile, and in the sixties and seventies, when my family’s story first became Italian, it was still the Edenic garden described in the seventeenth century by one lone traveller arriving over the mountains from Tuscany into what was then the Duchy of Modena and Ferrara. Our house nestled against a dyke that towers in my memory like a small mountain. It protected us from the river’s moods, and upon it cherry trees grew. Life was all earwigs in your ears, scorpions in your trousers and lots of biffing around in the undergrowth.

On the day in question, I am told, I went missing. The alarm was raised, everything was panic. My mother was beside herself with worry. For three hours family and neighbours searched high and low and imagined all the terrible things that could happen to a two-year-old alone in the countryside. Until my sister, then around ten years old, had an illumination. Without saying a word to anyone, she climbed the dyke and explored along the edge of the river, fearing the absolute worst. She found me at the waterline, sitting peaceably in a nest of reeds simply gazing into the swirling currents before me, oblivious to the pandaemonium I had caused. That was, I like to think, my first experience of silent transmission, the river my teacher.

In Zen, but not only8, silent transmission is fundamental to the teaching. When we think about the non-dual, we are forced to accept that there is nothing we can actually say about it. ‘The Dao that can be spoken is not the eternal Dao,’ state the famous first words of the Tao Te Ching. The sphere of experience, however, vaster in scope than language and categorically separate from it, is a place where we are free to dance to the tune of paradox without being undone by it. A late twelfth-century to early-thirteenth century commentator to the Wu-men kuan (Japanese Mumonkan), Wu-men Hu-k’ai, likens the experience of realisation to that of a deaf-mute having a dream. In other words, where the language falls short, experience continues, and through silent transmission subtler pathways than those offered by words and sentences may be found for it to migrate from one individual to another. It takes but a heartfelt smile to make one’s day.

In one of the root teachings on silent transmission in the Zen tradition, the Flower Sermon, the Buddha addresses the sangha on Vulture Peak by silently raising a flower. Of all the people gathered there to listen to him speak, only one, Mahākāśyapa, smiles in recognition, and to him the Buddha accords the gift of the transmission:

I possess the treasury of the true Dharma eye, the wondrous mind of nirvāna, the subtle dharma-gate born of the formlessness of true form, not established on words or letters, a special transmission outside of the teaching. I bequeath it to Mahākāśyapa9.

The story is not a direct transcription of a teaching of the Buddha’s such as we find in the Pali Canon. It is in fact in all likelihood the result of efforts to establish credibility and authenticity for the teachings of the Ch’an tradition (the Chinese precursor of Zen) by T’ang and Sung dynasty commentators at some point between the seventh and thirteenth centuries of the common era. Its apocryphal nature, however, does not detract from its power as an emblem, an object of contemplation which serves to focus and train the mind. It invites not interpretation, but silent acceptance of something, or nothing: either we get it or we don’t, but the ultimate logos, in the Heraclitean sense, remains one and the same: between the extremes of one thing and the other, there is the whole dialectic of history leading to a unity of opposites, or realisation.

Recently I returned to the aikido mat after a long, only partly Covid-related hiatus. There have been a few such pauses in the course of what is already a three decade-long voyage in the art. I am no model student. Yet I always come back, somewhere, wherever that happens to be, and here I am again, stepping onto a new mat in a new dojo, facing a new kamisama with yet another black-and-white photograph of aikido’s founder, Morihei Ueshiba, O-Sensei, floating on the wall above it. Here I am again, bowing to that picture as if to a familiar, much-loved keeper of sacred vows, the only constant in my aikido heart throughout all those years of training and not training.

As I kneel in seiza for the salute, I glance at the Venerable Teacher, as I always do when returning after a long absence, asking permission to train, acknowledging my many shortcomings before the only witness who sees them for what they are. I feel spacious, expansive, open to the known-unknown that lies before me. I am happy to be training in a beginner’s class again. In aikido, as in other martial arts, there are rituals of commencement and ending. There is etiquette during the training. I have had plenty of doubts over the years about the authenticity of observing rituals that do not belong to our culture, but not this evening. There is something sacramental about such new beginnings and my mind is at peace with the situation. When I left home to walk the silent woodland miles to the dojo, I slipped Suzuki-roshi’s classic on beginnings, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind, into my bag along with my journal—not because I anticipated finding time to open them, but because I felt they needed to be with me to mark the occasion. It is the pilgrim’s old trick of propitiating the way ahead with talismans.

The mat is a place of silent communion. O-Sensei used to say that there can be no dojo without the kamisama, the shrine, to anchor the space and the people moving within the space in a true dimension of practice. He was quite firm on this point. To train without the right ‘spirit’ is to not train at all, or worse, to train with the wrong intention. When the right intention is held by the teachers and the advanced practitioners, beginners may feel that all the anxiety and confusion finds its place of belonging. This is all part of the silent transmission of the mat. With masks, the mouth, vehicle of words and grimaces and smiles, is constrained, and our eyes become more focussed and skilful. With our mouths veiled, we are somehow freer to explore a connective immediacy with our training partner because we put a distance between ourselves and the busyness of mind. In so doing we note how the eyes and the mouth put the lie to one another; but we also note that we inhabit a vaster horizon of possibility once that misalignment is resolved. But let’s not kid ourselves: masks are a nuisance.

There is a note of dualism in the language here: does one inhabit a vaster horizon of possibility? Is that, a subject relating to a place, really the essential quality of the experience? Would it not be fairer to say that one is a vaster horizon of possibility, as well as inhabiting it? That presence and presence-in are two complementary aspects of one thing? This would seem truer of the experience of self as of something not owned, not defined, nor even definable, yet there, or here, nonetheless; not one thing, nor many. Just itself, beyond description. In those first moments of training on the mat, before physical tiredness narrows the focus of our attention, there is careful studied movement around the point of contact with the partner, an awareness of the space around us and the presence of others moving through it, of the ever imponderable, shifting mystery of cloud-formation, humidity and sunshine outside. There is a sense that consciousness contains the moment, and everything that can be named, but is not defined by it. Shaped, perhaps, even touched, but not fixed in any way; that consciousness is a marvelling-at, a rejoicing in the ceaseless, interdependent unfolding of creation upon which individual existence is but a ripple of light caught briefly on the surface of a stream. Everything around us is the lotus flower in the hand of the Buddha, a form signifying the formless.

We live through the body, but it is not only the body’s story we tell through the living of our lives. This is where we reach the outer limit of Everyman’s story and must resort to other narratives to carry us forward. Both dimensions, the dual and the non-dual, are integral to our individual nature, and on that basis we could found a whole new understanding of our relational experience, which is all of our experience. In such a view, we would probably be less inclined to exploit everything we touch, because exploitation requires first that we make a separation between what we want and don’t want at the expense of the integrity of something other than ourselves—including our own integrity as human persons. This is the value of David Braine’s holism. The question then becomes: can we take it all the way to include everything, from the biological to the metaphysical, without falling into the trap of discriminating against those who don’t conform or comply? Probably not, but it is a worthwhile cause nonetheless.

Notes

1 Arendt, H. (2015) Ich slebst, auch ich tanze. Munich: Piper, n.38

2 Braine, D. (1993) The Human Person. London: Duckworth, p.14

3 Braine, ibid., p.20

4 See Mary Portas on the kindness economy on TED Talk, https://www.ted.com/talks/mary_portas_welcome_to_the_kindness_economy; and in her new book, Rebuild: how to thrive in the kindness economy (2021) Transworld Digital.

5 See the following document from the Pontifical Council: ‘Gesu Cristo Portatore dell’Acqua Viva: una riflessione cristiana sul ‘New Age,‘ https://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/pontifical_councils/interelg/documents/rc_pc_interelg_doc_20030203_new-age_it.html#3.2.%20Narcisismo%20spirituale? For an overview of orthodox Catholic views on this topic, see ‘Lo Yoga è un rischio per la salute spirituale’, Famiglia Cristiana, 26 February 2015, https://www.famigliacristiana.it/articolo/lo-yoga-e-un-rischio-per-la-salute-spirituale.aspx. Lastly, for insight into the positions adopted against so-called ‘alternative’ forms of spiritualism by the Catholic clergy, see Religiosità Alternative, Sette e Spiritualismo: sfida culturale, educativa e religiosa, a report on the conference of bishops held in Rimini in 2013: http://www.gris-rimini.it/documenti/magistero/confepiscromagna/Religiosita_alternativa_2013.pdf

6 This is touched on, for example, in Adam Curtis (2021) new six-part documentary series, Can’t Get You Out Of My Head.

7 An eloquent commentary on this last point can be found in George Steiner’s controversial 1959 essay, ‘The Hollow Miracle.’ The essay studies the dehumanisation of the German language following the rise of Nazism.

8 It is a real question whether such examples, taken from history and literature, should still be used, when it is clear that in the sixteenth century it was possible to talk about an idea of ‘Everyman’ because by far the most dominant constituency in most societies was white and male. My interest is how we talk about such figures, not whether or not they should be cancelled.

9 Jung, C. G., Kerényi, C. (2005) Essays on a Science of Mythology: The Myth of the Divine Child and the Mysteries of Eleusis. London: Routledge.

‘One day the Buddha silently held up a flower before the assembled throng of his disciples. This was the famous “Flower Sermon.” Formally speaking, much the same thing happened in Eleusis when a mown ear of grain was silently shown. Even if our interpretation of this symbol is erroneous, the fact remains that a mown ear was shown in the course of the mysteries and that this kind of “wordless sermon” was the sole form of instruction in Eleusis which we may assume with certainty.’

10 Welter, A. ‘Mahākāśyapa’s Smile: Silent Transmission and the Kung-an (kōan) Tradition’ in Heine, S., Wright, D.S. (eds.), (2000) The Kōan: Texts and Contexts in Zen Buddhism. Oxford: OUP.